Every dilemma carries a paradox at its heart. If one option were clearly good and the other clearly bad, it wouldn’t feel like much of a dilemma at all. Instead, both paths often carry a certain appeal, and both can be justified in different ways. That’s what makes the decision difficult: you are left to weigh not just right versus wrong, but wise versus wiser, or relevant versus timeless.

In Shona culture, as in many others, people often turn to proverbs when facing uncertainty. Proverbs are compact capsules of wisdom, handed down through generations. They draw from the lived experience of ancestors, distilling observation into guiding truths. Yet here lies a fascinating tension: Shona proverbs don’t always line up neatly in one direction. For almost every proverb that points you one way, there’s another that seems to tug you in the opposite direction.

This is not a weakness of the tradition, but rather its strength. Proverbs mirror life itself — complex, layered, and rarely reducible to one-size-fits-all advice. They push us to think critically and apply wisdom according to circumstance.

Below, I share 20 Shona proverbs arranged in pairs that appear to contradict one another. Each pair captures this tug-of-war of wisdom, where truth is not about absolutes but about context.

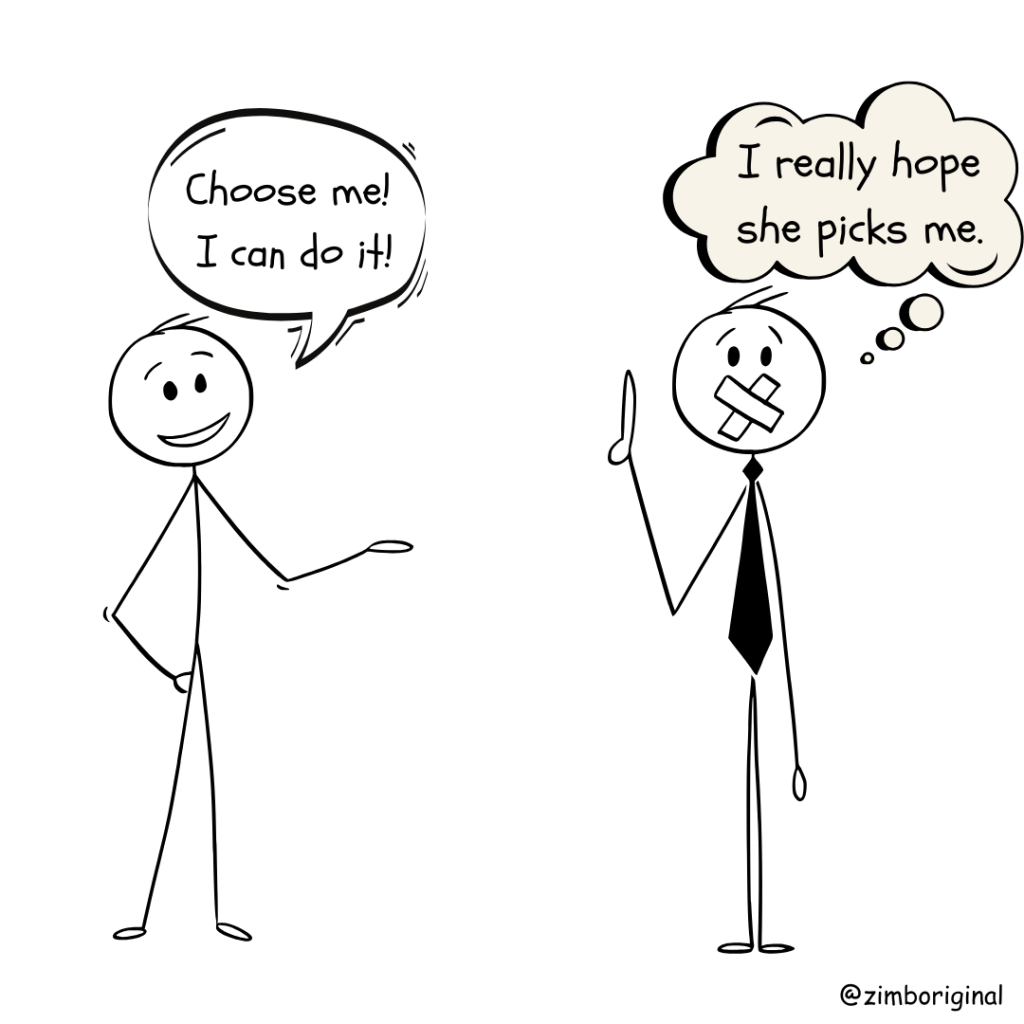

1. Mwana asingacheme anofira mumbereko.

A child who does not cry while on their mother’s back will die quietly.

2. Chitanduro ndaamai, mugoti unopiwa anyerere.

It is from a mother’s wisdom that the cooking stick is given to the quiet one (so that the child may lick it).

Should you speak up to get what you need, or wait quietly and trust that recognition will come to the deserving? The first proverb warns that silence can leave needs unmet, while the second suggests that patience and discretion may earn rewards from those who truly understand. Together, they capture the dilemma between advocating for yourself and trusting the wisdom of timing.

The balance lies in knowing when it’s necessary to speak up and when it’s wiser to wait — weighing the situation and the people involved.

Outside his father’s territory, the son of a chief is a servant.

4. Chikomo chiremera kune vari kure, vari pedyo vanotamba nacho.

A mountain commands awe from those far away, but those who are near treat it lightly.

Is your status respected by outsiders as much as by those who know you? Should you always assert it, or accept that familiarity can make even the important seem ordinary? And sometimes, outsiders may not care either. The first proverb reminds us that outside your own sphere of authority, you may have to adapt and accept a lower status. The second shows that even those in positions of power or significance may be taken for granted by those closest to them.

The balance lies in understanding context: honor and humility go hand in hand, depending on where you are and who you are with.

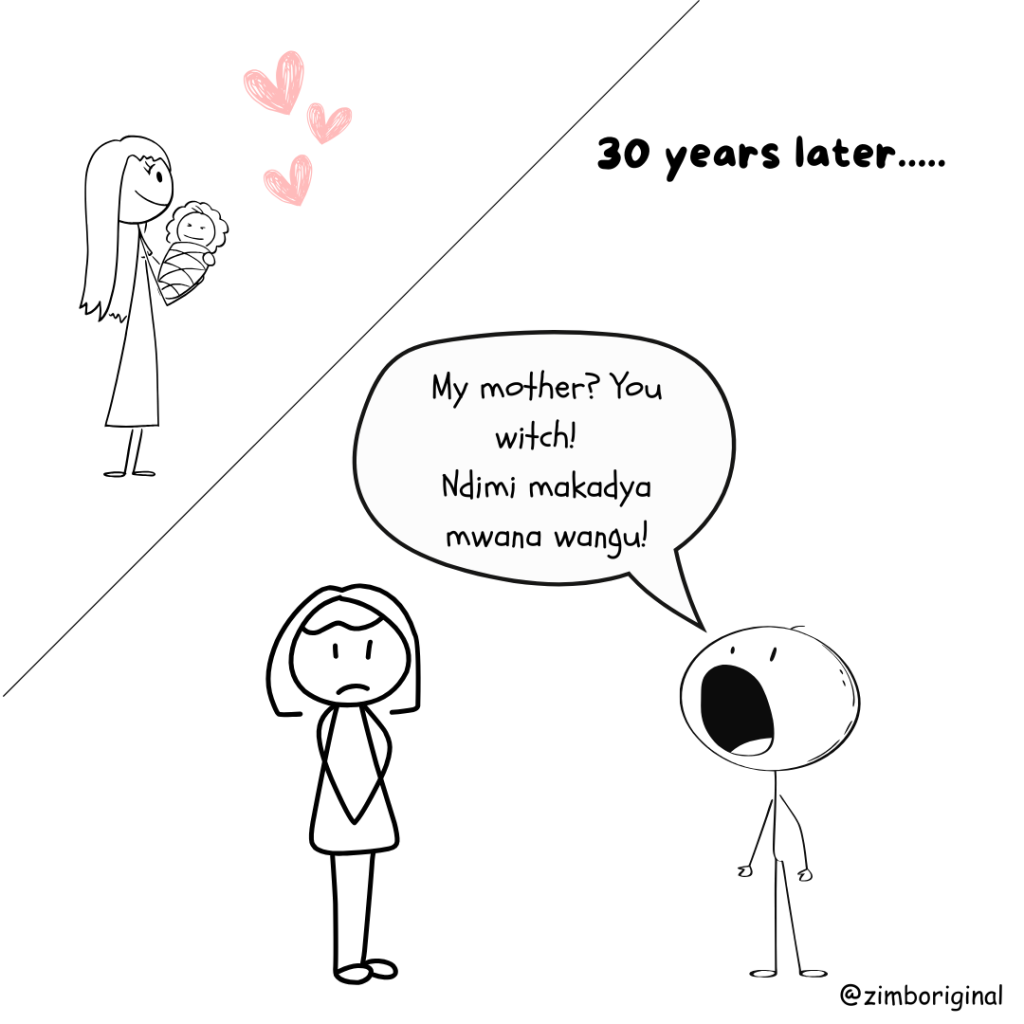

5. Chirere, mangwana chigozokurerawo.

Raise it well, and it will do the same for you tomorrow.

6. Kurera imbwa nomukaka, mangwana inofuma yokuruma.

Raise a dog on milk, and tomorrow it may bite you.

Should you invest care and trust in someone, or protect yourself against potential betrayal? The first proverb encourages nurturing others, showing that kindness and guidance can be repaid in the future. The second warns that even those we help may turn against us unexpectedly.

The balance lies in giving care thoughtfully—nurture and support, but remain aware that outcomes are not always guaranteed.

7. Mbeva zhinji hadzina mashe.

Too many mice have no lining for their nest.

8. Chara chimwe hachitswanyi inda.

One finger cannot crush a louse.

Is it better to work alone to avoid crowding and conflict, or to collaborate because success often requires teamwork? The first proverb warns that too many people involved in a task can dilute resources and hinder progress. The second reminds us that some challenges cannot be tackled alone and require cooperation.

The balance lies in finding the right number of people for the task — enough to achieve the goal, but not so many that coordination breaks down.

9. Chinono chine ngwe, bere rakadya richifamba.

Slowness is a trait of the leopard, a hyena had its meal while in motion.

10. Mandikurumidze akabara mandinonoke.

Too much speed breeds delay.

Should you act quickly to seize an opportunity, or slow down to avoid mistakes? The first proverb emphasizes prompt action, showing that hesitation can cause you to miss out, like a hyena finishing a meal while the leopard moves slowly. The second warns that rushing can backfire, turning haste into delay.

The balance lies in acting decisively but thoughtfully — moving quickly when the moment calls for it, yet avoiding careless haste.

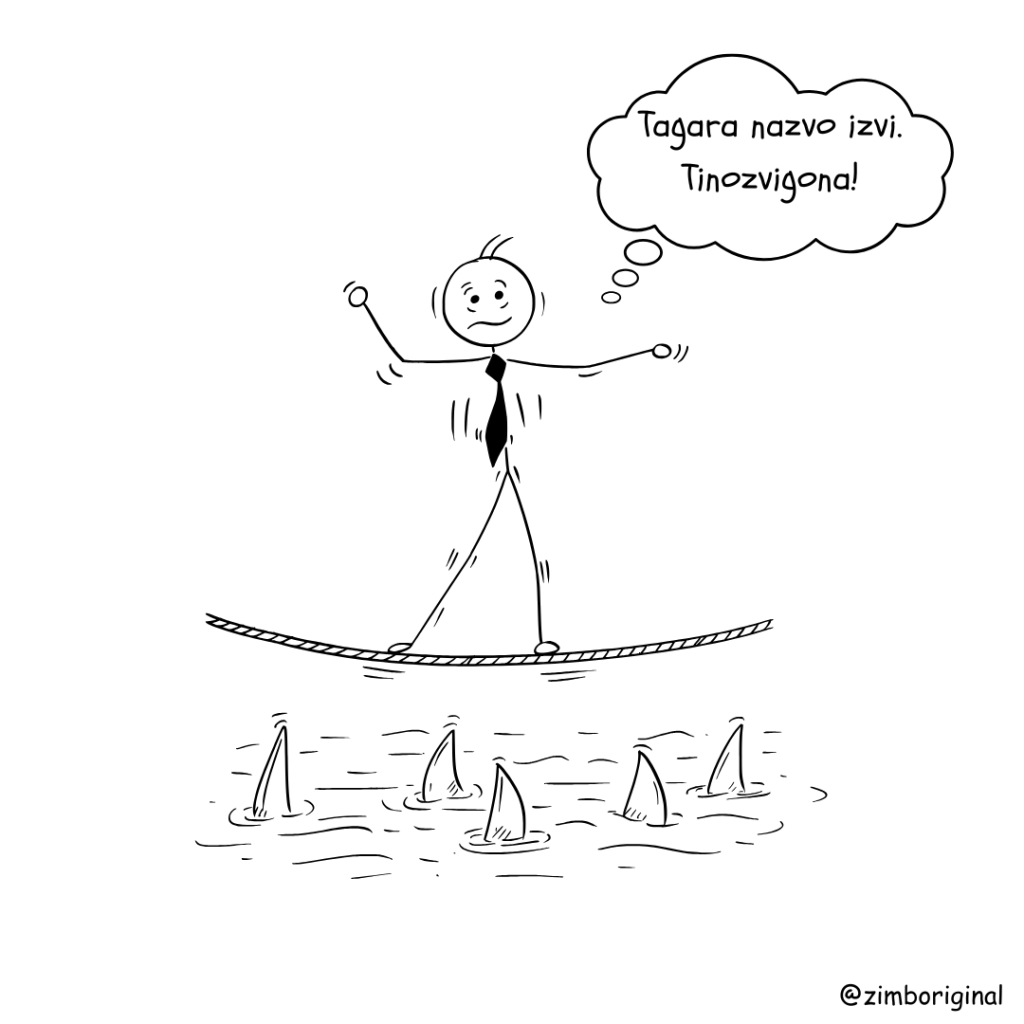

11. Agumhina afamba, hazvienzani naTigere.

One who has limped has walked, unlike the one who remains seated.

12. Masukamukanwa, bere harirariri mapapata emhashu.

A locust is just a titbit and nowhere near enough for a hyena’s evening meal.

Is any help valuable, or only help that is substantial enough to make a real difference? The first proverb reminds us to appreciate even small contributions, since they still move things forward. The second warns that too little help may be practically useless, like a locust feeding a hyena.

The balance lies in recognizing and valuing effort, while also being aware of when the support provided is genuinely sufficient for the task at hand.

13. Charovedzera charovedzera, gudo rakakwira mawere kwasviba.

What one has become accustomed to takes root; a baboon climbed a steep rock face in the dark.

14. Chimedzamatore akadzipwa nebvupa remhuru.

One known to swallow the (tough) meat of an old beast, choked on the bone of a calf.

Should you rely on experience to handle challenges, or remain cautious even when things seem easier than before? The first proverb highlights how familiarity and skill allow one to succeed under difficult conditions, like a baboon climbing a steep rock face in the dark. The second warns that what seems simple or smaller can still present unexpected obstacles, like choking on the bone of a young calf.

The balance lies in trusting your experience while staying alert to new risks, even when a task appears easier than those you’ve tackled before.

15. Chivi chinodya mwene wacho.

Wrongdoing consumes the wrongdoer.

16. Chivi hachivingi mumwe, asi vose.

Adversity befalls not only one, but all.

Is wrongdoing a burden only to the wrongdoer, or does it affect everyone around them? The first proverb emphasizes personal accountability, showing that immoral actions primarily harm the one who commits them. The second reminds us that the consequences of misdeeds or adversity often ripple outward, impacting family and community.

The balance lies in recognizing both personal responsibility and the wider effects of our actions, understanding that our choices rarely exist in isolation.

17. Chiripo chariuraya, zizi harifi roga nemhepo.

Something must have killed it, an owl doesn’t just die due to the wind.

18. Kana museve woda nyama unodauka wega pauta.

When the arrow craves meat, it springs off the bow on its own.

When something unusual happens, should we look for a clear cause, or accept that some events occur without explanation? The first proverb insists that every outcome has a cause, emphasizing investigation and accountability. The second suggests that some occurrences seem to happen spontaneously, beyond obvious reason.

The balance lies in being curious and seeking understanding, while also accepting that not everything has a cause in the way we know.

19. Kuzengurira izwi romukuru kuramba mhangwa.

To shun an elder’s voice is to reject advice.

Receive advice with your own ideas in mind.

Should you follow the advice of elders without question, or weigh it against your own ideas? The first proverb warns that ignoring the guidance of those more experienced is unwise. The second reminds us to receive advice thoughtfully, keeping our own judgment in mind.

The balance lies in respecting guidance while exercising personal discernment — learning from others without losing your own perspective.

Finding balance in contradiction

The contradictions in Shona proverbs reflect the contradictions in life. They don’t cancel each other out; instead, they form a mosaic of wisdom that requires judgment, timing, and context. When faced with dilemmas, the question is rarely which proverb is ‘right,’ but which applies to the moment at hand.

Perhaps the real wisdom lies not in expecting one answer to fit all, but in learning to sit with the tension — and from there, to decide.

Do you know a pair of tsumo that seem to contradict each other? Share them in the comments — I’d love to hear your examples!

Related Reads: