I have to be honest, this is one topic I wish I didn’t have to discuss. But there’s no way I can talk about Shona culture, customs, beliefs, and religion without eventually talking about uroyi (witchcraft), practised by varoyi (witches).

Like in many parts of Africa, beliefs around witchcraft are widespread and deeply ingrained among the Shona. They shape how society functions and continue to be passed down through generations, even among those far removed from the practices themselves. These beliefs have traveled with Zimbabwean communities across borders and touch nearly every aspect of Shona life, from personal matters to seemingly random events.

As a Shona woman deeply connected to my identity and heritage, I’ve experienced firsthand the weight of these beliefs. I’ve realized that, more often than not, people turn to witchcraft as an explanation when they are unwilling to think critically or consider other perspectives. When my passion, background, and even my flaws were scrutinized and cast under suspicion, I chose not to dwell on the negativity. Instead, I accepted that everyone’s beliefs are their own, just as our dying is our own. Since I cannot control what others think or say about me, I focus on what I can control: how I respond.

Enough about me. Let’s explore some of the surprising beliefs around witchcraft that are common among us—the Shona people.

The Shona believe witchcraft causes illness and death

It is common for serious illness or death to raise suspicions of witchcraft. People may believe that someone, a rival or even a jealous relative, is responsible for their misfortune.

Michael Gelfand’s 1967 medical journal article provides some insight. In 35 case records of alleged witchcraft between 1899 and 1930, 7 involved sickness and 17 involved deaths. In a later series of 90 cases recorded between 1959 and 1963, there were 21 illnesses and 46 deaths. Of these, 10 cases involved attacks on children in the earlier series, and 40 in the later one.

Suspicion often grows when a series of deaths, say in a family, happens and cannot be explained. Recently, I watched a video of a medical doctor discussing hereditary conditions, like high blood pressure, that can cause repeated sudden deaths in families.

Surprisingly, even with modern medicine and abundant information, some families continue to blame witchcraft instead of seeking medical explanations.

The Shona believe prosperity can come through witchcraft

While accusations of witchcraft are widespread among the Shona, fewer people are accused of practising the classic form of uroyi. The classic form is often described in dramatic terms: witches wake at night, ride on hyenas, and even feed on the flesh of the dead. The accusations that come up more often are linked to another form—using spells to gain prosperity. This form is considered especially dangerous because the benefits supposedly come at the expense of others, leading to illness, death, or poverty within the family.

So, already, we can see that witchcraft is not viewed as a single activity but as having multiple forms, each with its own features and consequences.

According to Tsodzo (1980: 97–98), the main forms of witchcraft include:

- Vanhu vanoita zvinhu zvakaipa — people who commit pure acts of evil, such as polluting a public water source or other such deliberate evil deeds.

- Varoyi vemadzinza — witches practising the classic form, believed to be passed down through family lines.

- Varoyi vekuromba — those who use spells to further a cause.

- Varoyi vemuchetura — those who poison others.

- N’anga — diviners who are consulted and provide harmful services.

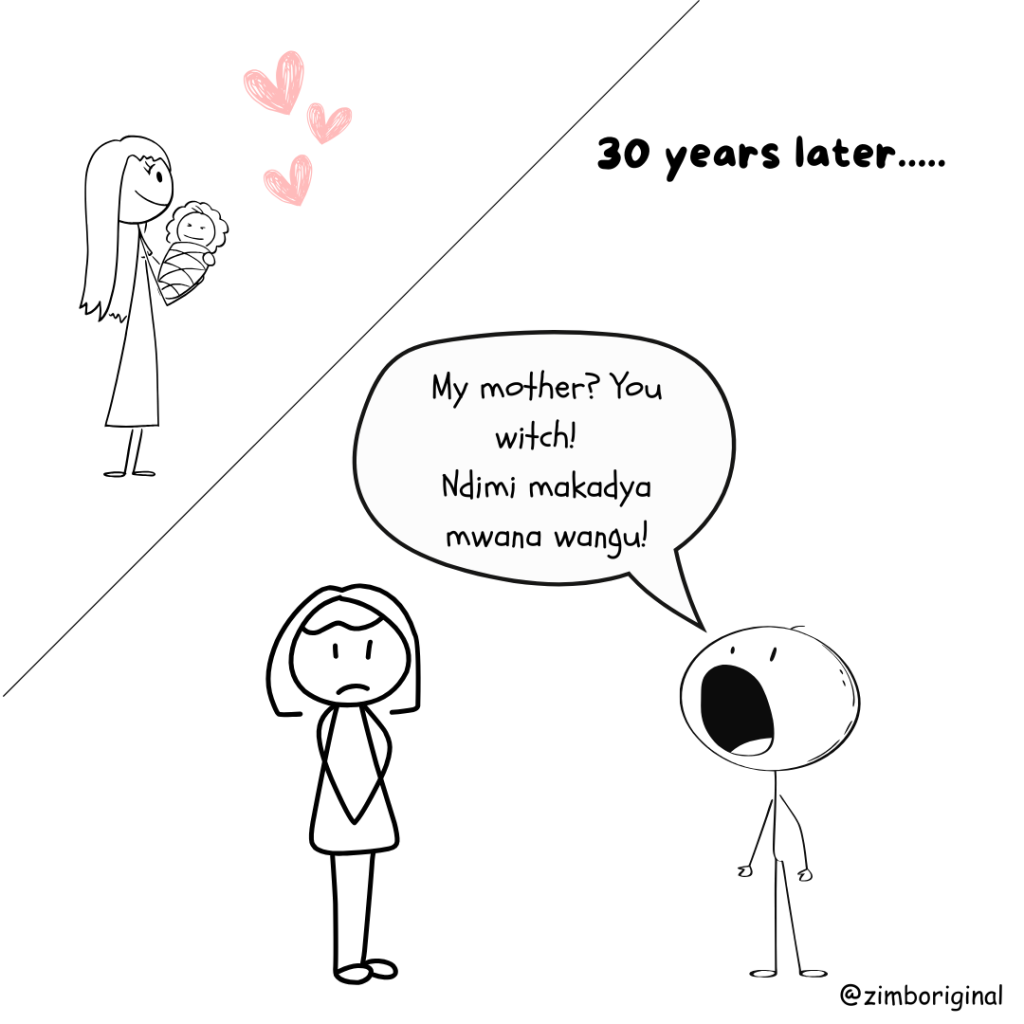

Accusations of witchcraft often tear families apart when one member is believed to prosper at the expense of others through charms or spells. These spells are thought to benefit the user while bringing harm to relatives in the form of serious illness, death, or poverty. In some cases, people have even gone as far as publicly accusing their own parents of being witches, blaming them for personal tragedies and misfortunes.

What makes these beliefs particularly striking is the aspect that witchcraft is not confined to the inherited form. As outlined earlier, anyone who is mean-spirited or just unlucky can be accused of practicing uroyi. Even parents who love their children deeply can be disowned or shunned if their children believe them to be witches. This unpredictability, where ordinary people can suddenly be labelled as witches, adds an unexpected and unsettling dimension to the way witchcraft beliefs shape Shona life.

The Shona believe witches use hyenas and snakes as their familiars

The classic witch I mentioned earlier is believed to ride hyenas during their nighttime gatherings, where they open graves and feast on the flesh of the dead. Witches are also said to keep company with snakes. A well-known Shona proverb captures this belief: Manomano emuroyi kunyepera kutya dzvinyu, iye akasungira nyoka muchiuno. (It is an act of deceit for a witch to panic at the sight of a lizard, while a snake is tied around their waist.)

But this raises an important question: has there ever been any real proof of these activities? Do these witches truly exist in the way tradition describes them?

In a 1986 paper, Mafico challenges some of the arguments made by Professor Chavunduka, who is widely remembered for his research and views on witchcraft. Mafico—like many other scholars before him—argues that belief in witches and witchcraft is essentially belief in a myth.

Surprisingly, even Chavunduka himself, the foremost authority on witchcraft, seemed to have doubts. As Mafico points out, Chavunduka admitted there were still many unanswered questions regarding witchcraft. These include questions regarding the different types of witches, the kinds of medicine said to be used in bewitching others, the reasons behind confessions that some people made in courts of law (which were sometimes later disproved by medical, police, sociological, and anthropological research), and so on.

Curiosity Matters

There are many other beliefs about witchcraft among the Shona, far more than I could cover in a single post. But I hope the glimpse I’ve shared here sparks your curiosity, not just about witchcraft, but about anything that makes you pause, wonder, and want to learn more.

Exploring witchcraft among the Shona reminds us of the power of stories, the weight of tradition, and the value of questioning what we hear. I can’t say for certain whether these accounts are myth or reality, but I do know that such conversations reveal valuable lessons about human behavior, fear, and morality.

Ultimately, understanding these beliefs shows us how culture shapes our world, and how curiosity can guide us toward deeper insight, empathy, and respect for perspectives that differ from our own.