Religion as a way of life: Reflections on Shona customs

While having a conversation with my sister the other day, one thing became quite apparent to me. The indigenous religion of the Shona people was not just a series of scheduled meetups designed to remind each other about ancestral spirits and the rules that people were supposed to follow — rules which, because of human frailty, would likely be broken and as such needed constant reinforcement.

Instead, the indigenous religion of the Shona people was a way of life. Religious practices were woven into the very fabric of family life, and within those practices lay the guidelines for how society was supposed to function. As a result, there was no need for occasional weekly meetups, because religion was lived every day.

However, when Shona society moved away from its indigenous religion, cracks began to appear in the governance of society. To some extent, these cracks were patched up through systems like the courts and other formal mechanisms of governance. Even so, this did not happen without its own challenges. Some aspects of life could be codified into law, but others could not.

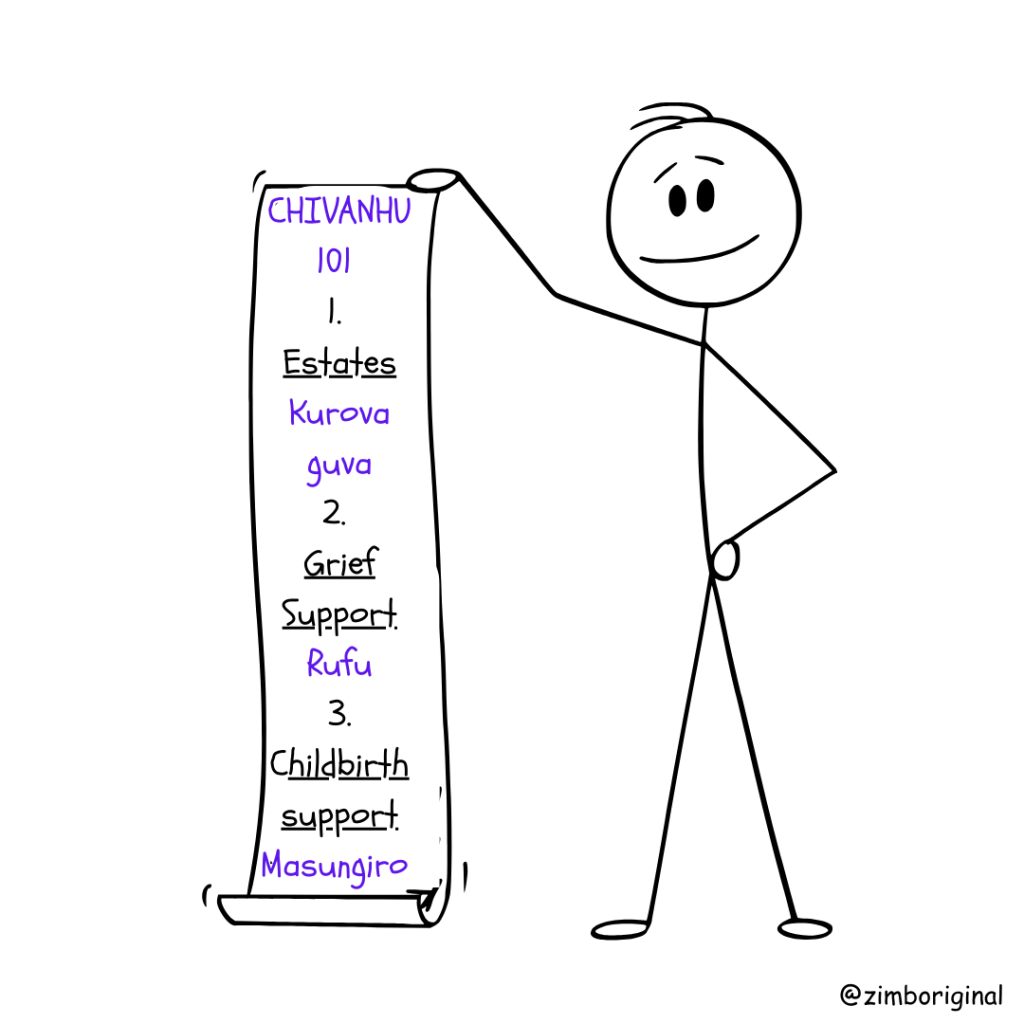

In this post, I want to explore a few customary practices that I know of, which have been retained in one form or another. These practices carry both religious elements and significant practical implications that once made them indispensable to the functioning of Shona society.

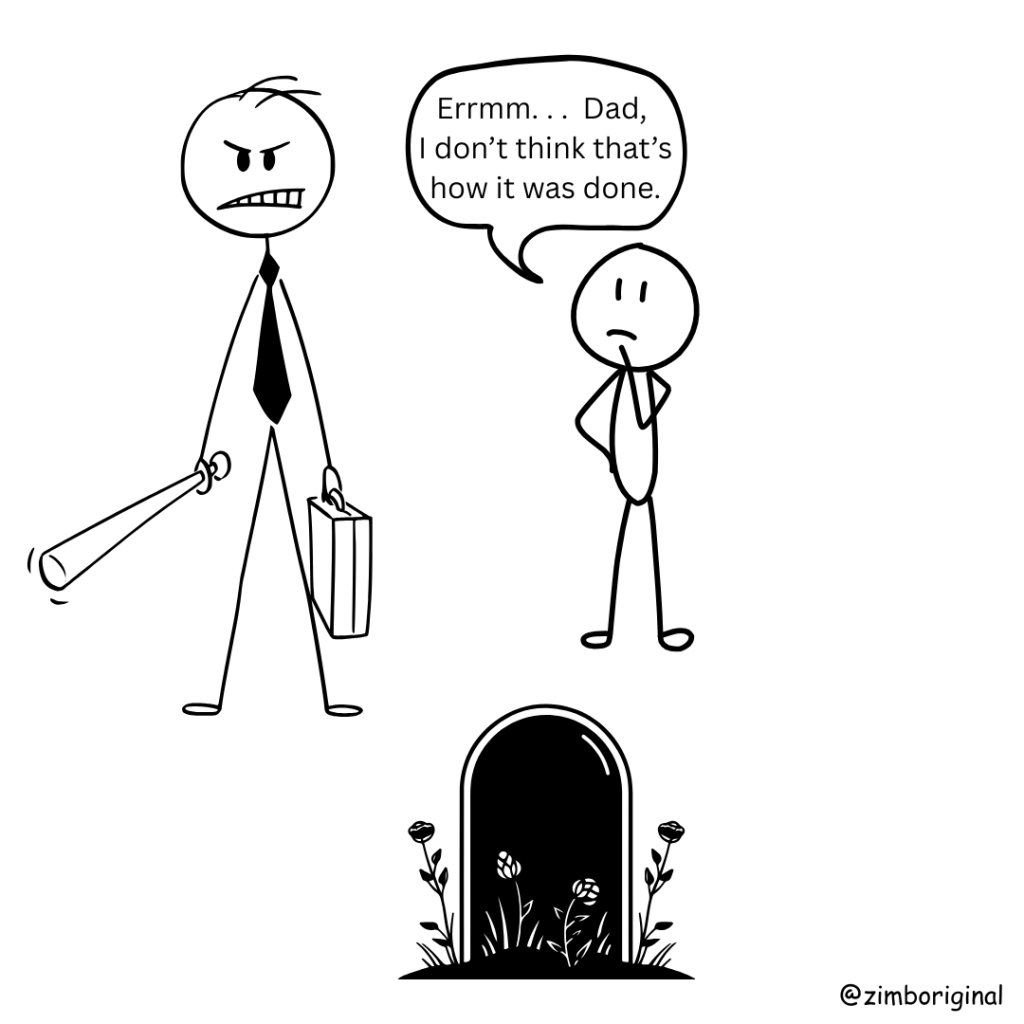

1. Kurova guva

This is a custom which many people today have abandoned, often because they now identify as Christians and see it as incompatible with their faith. The religious aspect of kurova guva involved rituals believed to ‘regularise’ the spirit of the deceased — bringing it from the grave so that it could formally join the community of ancestral spirits. Once accepted, the spirit could then watch over the surviving family.

But the custom also had very practical dimensions. It created a structured process through which the extended family could formally appoint someone to take responsibility for the deceased’s household. However, this was not without its complications. In some cases, the deceased’s wife was ‘inherited’ by a male relative, which led to jealousy, conflict, and — with the advent of HIV/AIDS — severe health risks and tragedies.

This raises an important question: without this custom, then, how do families today deal with the responsibilities left behind after the loss of a provider? I guess the answer lies in how modern society is different. Where a man dies – a husband and father, many widows today are fully capable of supporting themselves and their children, so at some point, the practicality of the custom seems to diminish. However, it cannot be ignored that Shona society is still largely patriarchal, and many people continue to value the sacredness of ties to their father’s lineage.

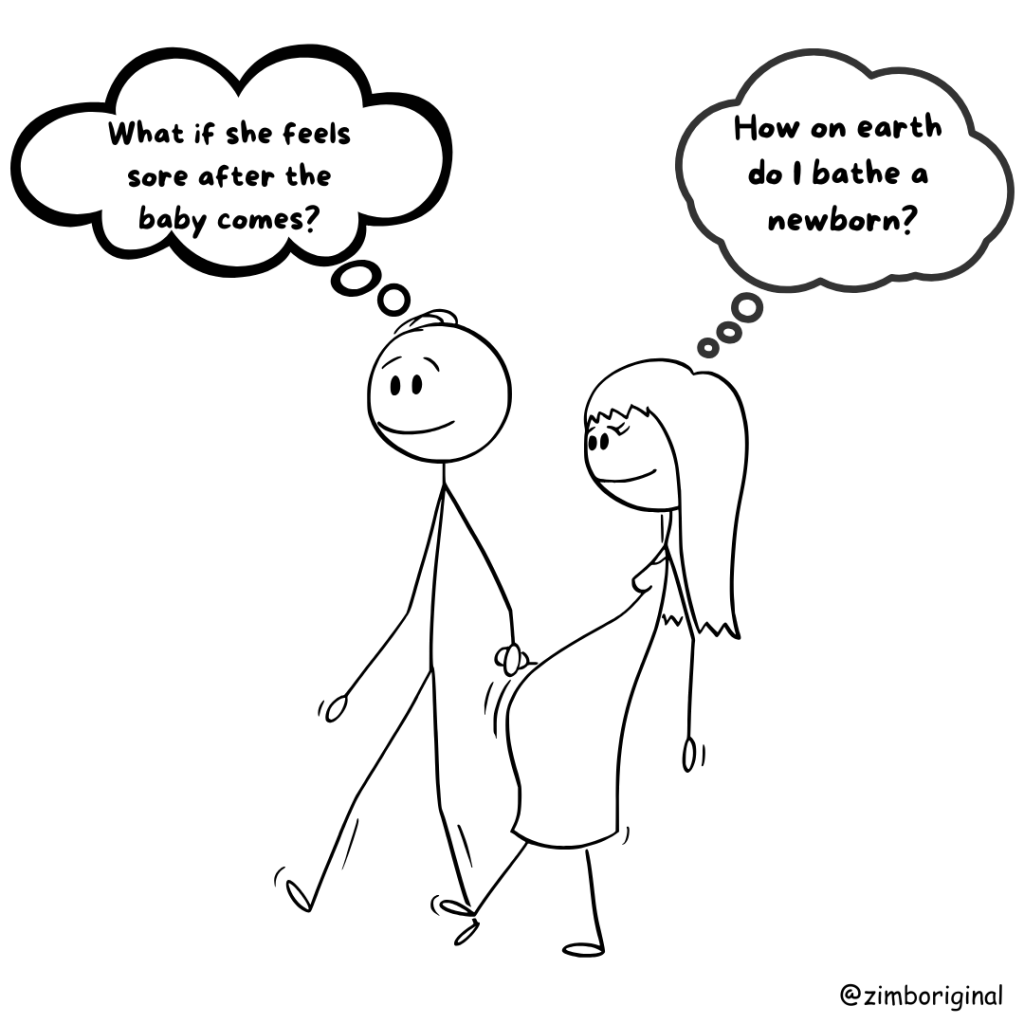

2. Masungiro

After a woman married customarily, and when she was expecting her first child, a ritual known as masungiro was performed. The husband would make a ritual offering to the woman’s parents — traditionally a cow, though more commonly today two goats. I’ve written more about this ritual in a separate post here.

The religious dimension of the practice — which has largely been overlooked in modern times — involved the woman’s mother dedicating the she-goat she received to her matrilineal ancestors. Until the ritual was performed, the expectant woman was not supposed to have contact with her family. Once it was completed, she could return to her parents and remain with them until after the child was born. During this time, her mother would also administer medicines and herbs intended to make the delivery safer and easier.

The practical purpose of masungiro was clear and vital. As a first-time mother, the woman needed guidance and support. The ritual ensured that she returned to her family home, where her mother and relatives would prepare her for childbirth. After the baby was born, her family — especially her mother — provided care and helped her adjust to motherhood.

Masungiro was therefore both spiritual and social. It linked the unborn child to the family’s ancestors while also creating a built-in support system for new mothers — something that remains relevant even today, in societies where young mothers often find themselves isolated.

3. Rufu

Shona funerals are perhaps the most ritual-laden of all cultural practices, full of religious and practical meaning. (I’ve explored some of these practices in more detail in another post here.) For generations, people clung to these traditional practices, but over time, many of them have faded, and their deeper significance is slowly being forgotten.

One of the most significant aspects of Shona funerals is the vigil. When a person dies, it is customary for the body to remain at least one night before burial. During this time, people gather, sing, dance, and play drums — sounds and rhythms strongly associated with Shona religious life. Interestingly, even among Christian communities, this custom is still widely observed.

The practical side of the vigil is often overlooked but extremely important. Spending a night with the body helped guard against premature burials. I personally know of a case where a woman’s family believed she ws dead, but a relative later realized they were still alive. Modern medicine helped confirm this, but in older times, the simple practice of waiting at least one night was a safeguard against burying someone alive.

Beyond this, the vigil served a profound social purpose. In particular, it ensured that the bereaved family was not left to grieve alone. Instead, the entire community came together, leaving behind their daily routines to provide presence, comfort, and solidarity. This collective grieving is powerful — imagine the difference between mourning in isolation versus being surrounded by people who share your pain, sing with you, and carry the weight of your sorrow. It is a practice that should never be taken lightly.

Final Thoughts

Looking at kurova guva, masungiro, and rufu, it becomes clear that for the Shona, religion was not a compartment of life set aside for certain days or ceremonies. Rather, it was life itself. These practices carried both spiritual meaning and practical value, helping families and communities navigate life’s greatest transitions: birth, death, and the responsibilities that lie between. Now I realise how fitting it is to refer to indigenous ways as chivanhu, which I would loosely translate as the practices of being human, or perhaps even better, being humane.

As society modernises, some of these customs have been discarded, while others survive in altered forms. Yet their legacy reminds us of an important truth: religion in Shona culture was not something separate from daily living. It was the framework that shaped relationships, responsibilities, and the very fabric of community.

And so, as we embrace new faiths and set aside the indigenous religion that once shaped us, we must pause and ask: what are we truly discarding? Without this foundation, we risk losing not only valuable customs but also the governance and cohesion of a society that gave us a strong and distinct identity. That identity is what nurtures unity of purpose, from which lasting economic strength thrives. While we can, and should, learn from others and grow wiser — we can still do so without losing ourselves.

Ultimately, we must never forget: the indigenous religion of the Shona was never merely about worship; it was the architecture that held our society together, gave it order, and enabled it to thrive.

Great insightful article, thanks for sharing

You’re welcome! Thanks for reading Bornaventure.

Love this

Thank you so much! I’m really glad you loved it 😊

I experienced morden versions of some of these practices. We didn’t have kurova guva however there was a tombstone unveiling for a man & then tete was appointed as ‘Sarapavana’ . Raising another interesting aspect of how siblings can replace each other in roles? Tete can act as your father & sekuru (mother’s brother) can represent your mother in her absence