I attended a kurova guva ceremony just this past month. A mbira crew had been hired to play, and the drummer’s surname was Mangoma. He explained that his great-great-grandfather had been a talented drummer, and that’s how the family got the name Mangoma. Ngoma is the Shona word for ‘drum.’ As he grew older, he too developed both a passion and a gift for drumming. That got me thinking about Shona names.

Years back, when I was in my second job, a young man from a company in our building murdered his girlfriend. His surname was Zimondi — and mhondi in Shona means ‘murderer.’ At the time, I thought it was a strange coincidence that his name matched his crime. But with time, I began noticing other patterns: surnames often seemed to echo a person’s personality, character, or even appearance.

I remember a girl in school whose surname hinted at her looks. You’d have had to see her yourself to decide whether it was fair, but the point stuck with me.

Over the years, I’ve come to believe it’s no accident. Shona surnames often capture traits, qualities, or histories that seem to persist in the family line. To understand this better, it’s worth taking a closer look at Shona names.

Shona first names

Let’s start with first names. My own name is Shungu. People often ask if it’s the beginning of a longer name — maybe Shunguadziurayi (‘anger doesn’t kill’). My official record just has the short version, but I was told the full name was indeed longer: Shungudzangu, meaning ‘my desire’ or ‘my deep yearning.’ To me, it carries a positive sense: a strong desire — determination.

The story behind it is really my father’s to tell, since he was the one who named me. And that’s the thing with Shona names: they carry stories. The bearer is often someone else’s message board. Of course, that’s not a problem if the story is good — and I like to think mine is.

I believe I’ve lived up to it. I am a go-getter. When I want something, I push for it relentlessly. In school, I was a straight-A student. Now, I’m working hard to build a meaningful business, and I know I won’t stop until I get there. In many ways, my name has manifested itself in my life.

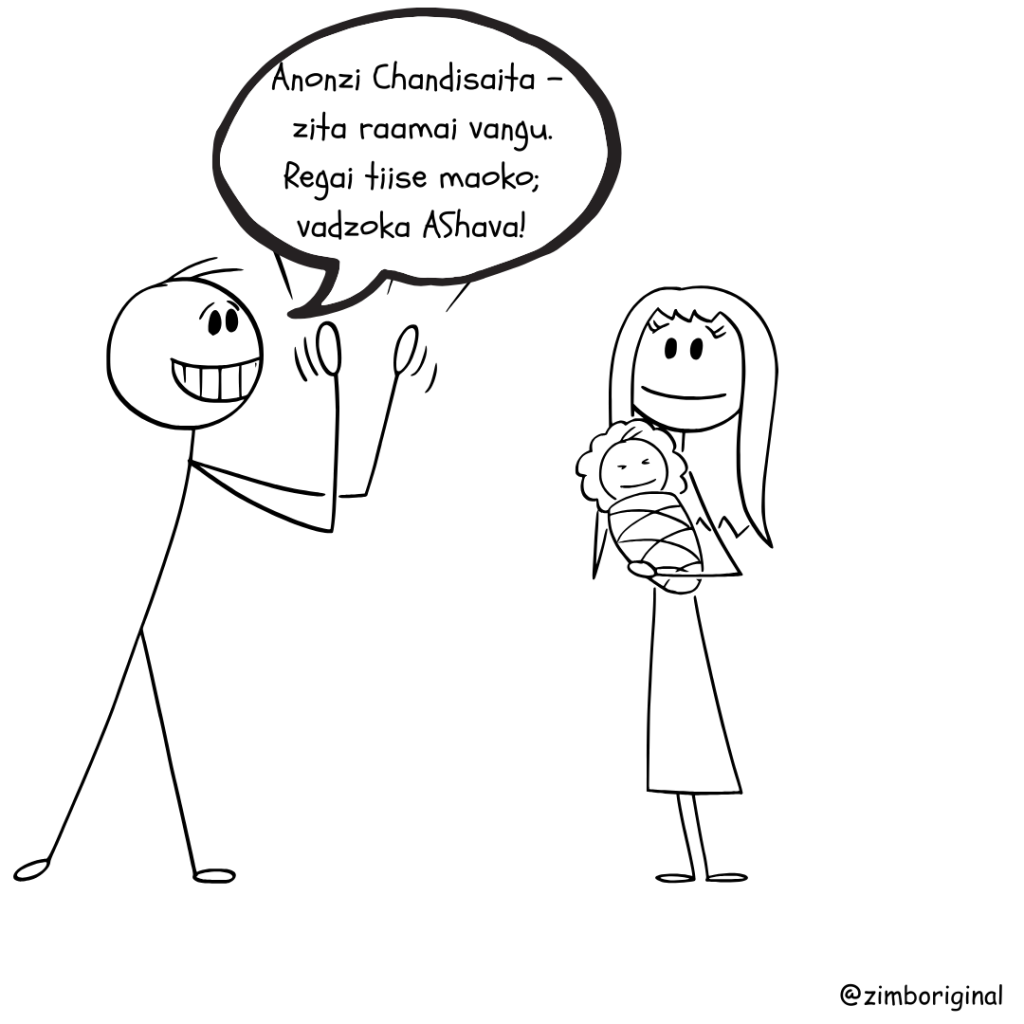

But not all names are that uplifting. Some speak of animosity, hardship, or family disputes. They are names given as messages between warring parties — names like Muchanyara (‘you shall be shamed’), Maidei (‘what did you want?’), Hazvinei (‘it doesn’t matter’), or Tapera (‘we are finished’).

Shona names often fall into a few broad categories. Some celebrate and serve as positive blessings for the bearer — for example, Tendai (‘give thanks’) and Rudo (‘love’). Others record circumstances, like Nyasha (‘grace’) or Mukundi (‘victor’) after a difficult birth. And some are used to protest, rebuke, or pass coded messages, such as Muchanyara or Hazvinei.

This diversity shows that in true Shona tradition, naming was never random — it was a deliberate act of storytelling, memory, and sometimes even confrontation. Even when English first names became common, outside of so-called Christian names, many retained this same storytelling spirit at their core — capturing hopes, experiences, or lessons. This makes it fascinating to see how Shona naming traditions continue even in names that are English.

English first names inspired by Shona traditions

I had never realized how distinctive English names among Zimbabweans were until I read an article about a leading global money transfer service. The company had repeatedly flagged transactions carried out by Zimbabweans as suspicious because their systems identified the names as seemingly random English words. But on further investigation, they discovered that these were indeed real names — not random entries.

This is where it gets interesting: names like Last, Nomatter, Bigboy, or Pretty may sound unusual at first glance, but they follow the same Shona naming tradition. Just like traditional Shona names, they carry meaning, intention, or a story. Rather than being chosen arbitrarily, these English first names are deeply symbolic, reflecting hopes, traits, or circumstances — a continuation of the age-old Shona practice of giving names that truly matter.

Shona surnames

I have always wondered how and when exactly the system of surnames came about. From what I’ve observed in my own family, it seems a surname can often be traced back to one of the family’s ancestors — typically following the paternal line — who was the original bearer of the name. Perhaps the surname coincided with the name of an ancestor who acted as the ‘father’ of the line when official documentation began, such as when the government started keeping registries.

For example, if Marimo was the patriarch, then when official documentation began, his children — say, Tapera and Munetsi — may have adopted Marimo as their surname. They would then appear as Tapera Marimo and Munetsi Marimo. Of course, this is just my speculation, not a confirmed fact.

Based on this line of thinking, I believe that to understand Shona surnames today, which often originated from the first names of ancestors, it helps to first take a closer look at the types of traditional Shona names that were given long ago. The name given often depended on the circumstances prevailing in the family or clan at the time of a child’s birth.

Traditional Shona names

According to a 2017 journal article by Alec Pongweni, The Impact of English on the Naming Practices of the Shona People of Zimbabwe, the following are the main types of traditional Shona names.

Zita remudumba

The maternity-home name — given to a child immediately after birth to welcome the new arrival and congratulate the parents.

Zita regombwa

The lineage or titular name — a name ‘surrounded by the spirits.’

Zita rejemedzwa

A name given at the suggestion of a diviner to calm a child who cried incessantly.

Zita remadunhurirwa

A nickname, often descriptive of someone’s character or habits. Such a name was usually given later in life, in addition to one of the earlier categories.

In the opening story of this post, I mentioned Mangoma — I imagine that is how this family’s surname came about.

Zita rechihani

A name given to mark an important event.

Zita rekudzandura

A replacement name, adopted by a family or individual to substitute any of the above — for example, if the original name was considered embarrassing.

Pongweni notes that the first four categories are based on the work of Professor George Kahari. I hope to get hold of his writings so that I better understand the nuances of each category. For instance, I know of cases where, at the suggestion of a diviner, a child was named after a deceased relative because the child faced delays in milestones such as speech or walking. It’s not clear which category such names would fall under.

Still, by looking at these types of traditional names, we can begin to make sense of many of today’s surnames, which were born from the first names of ancestors.

How names were coined

In creating names, there was often a playful creativity with words and word forms — as we can see in many surnames today. I’ve always been amazed by the ingenuity of our forefathers in this regard. These days, humanity in general seems less creative — just think of the contrast between past and present architecture. And with the rise of AI, I sometimes shudder to imagine what kind of creativity will be left for our children.

But let me not digress. Back to Shona names. Here are a few examples, some drawn from Pongweni’s work:

Chabayanzara comes from a playful word exchange. Someone might ask, ‘Chabaya chii?‘ (‘What has struck you?’), and the reply would be, ‘Chabaya inzara‘ (‘It is hunger that has struck’). The name then emerges as the shortened form: Chabayanzara.

There are also names where spelling differences reflect dialectal variation rather than short forms — for example, Mavenganise and Maenganise.

Other names, like Muzanenhamo, use Shona forms that today would be considered archaic. In this case, -za once meant -uya (‘to come’). So Mu-za-ne-nhamo essentially means Mu-uya-ne-nhamo — ‘the one who comes with suffering.’

This shows that understanding the linguistic structure of Shona names is key to fully grasping their meaning.

What it all means

Shona names carry layers of history, language, and lived experience. Whether born out of circumstance, wordplay, or ancestral legacy, each name is a story in itself. In their meanings we glimpse the worldview, struggles, and values of the Shona people. And as long as the names are spoken, the people’s story will never fade — echoing across time, binding past to present, and present to future.

Interesting article. My last name means a hunter. Zveshuwa handidi hangu nhamo or nzara. I work hard for a soft life😁. Most of my siblings and cousins are the same. We all work hard and hustle like hunters in our different professions. Except for one lazy brother anoda hake kufeedwer akagara sehonye. Is he the exception or should we doubt his paternity 🤔😂

Hahaha, I really enjoyed reading your comment 😄. It’s fascinating how your surname truly reflects your family’s hardworking spirit—hunters through and through! As for that one brother, every clan has its exceptions 🤭😂. Maybe he balances out the energy in his own way.

Thanks for sharing, I loved this!