Learning Shona — or any language — is more than memorising vocabulary and rules. It’s about building the confidence and mental habits that allow you to actually use the language in real life.

Unfortunately, even the most enthusiastic learners can get derailed by things in their environment — and sometimes by the very people trying to help them. These obstacles often show up quietly, and if no one notices them, they slowly drain motivation until the learner stops trying altogether.

I’ve seen it happen, and I’ve experienced it myself. Many years ago, I tried learning Ndebele. The clicks fascinated me — but they also terrified me. My housemates would laugh their lungs out whenever I fumbled a sound. At first, I laughed along. But deep down, I started speaking less and less… until I just gave up.

That experience stuck with me. It made me realise that small behaviours — a laugh here, an unnecessary rescue there — can make the difference between a thriving language learner and one who quietly quits.

So, if you’re teaching, mentoring, parenting, or even just interacting with someone learning Shona, here are 7 things to avoid if you want to keep their progress steady.

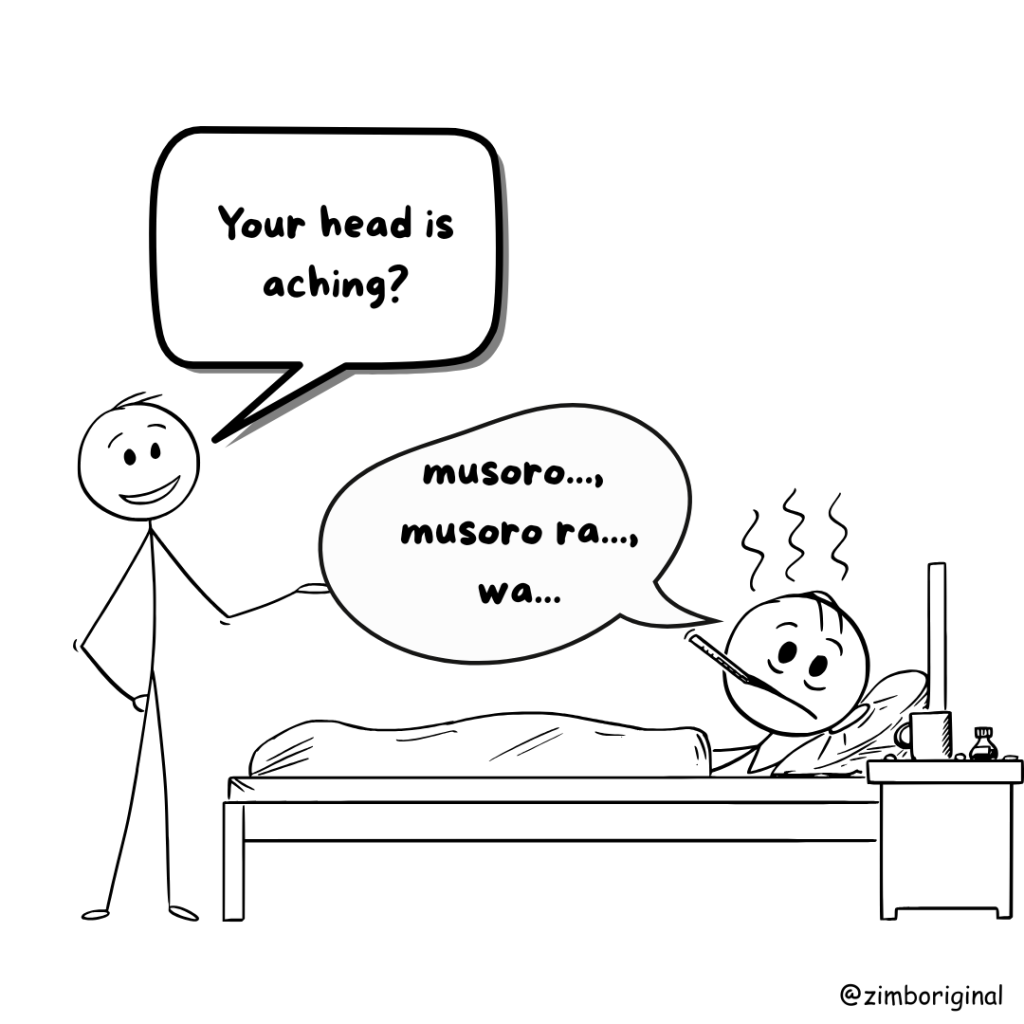

1. Laughing at Mistakes

Mistakes are part of the learning process — they’re proof that a learner is actively trying. But to the person making them, they can feel like public failure.

Laughing (even playfully) can hit harder than you think. The learner may stop taking risks, which is a death sentence for language growth.

What to do instead:

- Smile and encourage. If you need to correct, do it gently: ‘Ah, almost — you say it like this…’

- Share your own learning mistakes if you’ve learned another language. It makes the learner feel less alone.

- Remember that a safe space to make mistakes is a powerful motivator.

2. Not Using the Language With Them

This one is surprisingly common. You know someone is learning Shona, but you never actually speak Shona with them. You default to English because it feels easier and faster.

The problem? Without real-life practice, the language stays in ‘lesson mode’ — something they study, but never really live.

One of the most effective ways to create natural practice is through story. When a learner hears or reads a story in Shona, they’re exposed to vocabulary, sentence patterns, and cultural context without it feeling like a ‘drill.’ If the story is engaging, the learner wants to understand — and that desire fuels learning.

That’s one of the reasons I built Zimboriginal’s library for children. It’s packed with colourful, engaging bilingual (Shona and English) stories that allow learners to encounter the language in context while enjoying the plot and characters. Parents and teachers can use these stories as a starting point for short Shona conversations, reinforcing what the learner hears and reads.

For Parents: 10 Minutes a Day With Stories Can Make a Big Difference

You don’t need hours of tutoring to help your child grow in Shona. Just a few minutes a day using story-based learning can build vocabulary, confidence, and love for the language. Here’s how:

- Pick a short story from Zimboriginal’s library – Even a story under 50 words works.

- Read together aloud – Let your child repeat words they recognise.

- Ask simple questions in Shona – ‘Chii ichi?’ (‘What is this?’)

- Point out familiar words – Highlight repeated words or phrases in the story.

- Act it out – Simple gestures or miming can help words stick.

- Praise effort, not perfection – Celebrate their attempts to speak, even if they make mistakes.

- Reread favourites – Repetition strengthens memory and confidence.

Tip: Even 10 minutes a day adds up. Over a month, your child will naturally start using words and phrases from the story in daily conversations — without drills or tests.

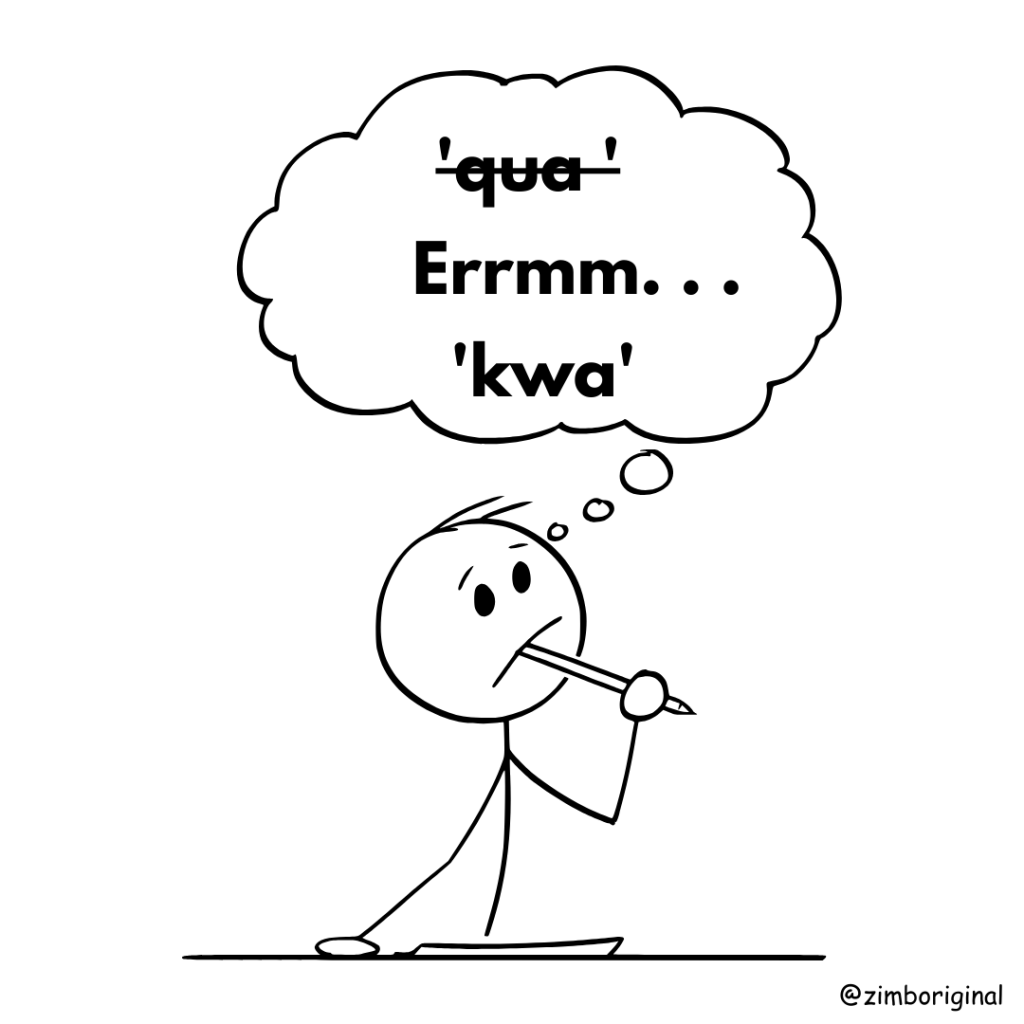

3. Rescuing Too Quickly by Switching to English

One of my favourite podcasters talks about ‘force functions’ — situations that force you to act, adapt, and grow. In language learning, this means letting the learner wrestle with the language instead of immediately switching to English.

When you rescue too quickly, you remove the struggle that makes the brain work to find the right words — and that struggle is where deep learning happens.

Stories can help here too. If you’ve read a story together, you can point back to a scene or a character when the learner is stuck. It’s a gentle nudge that keeps them thinking in Shona without shutting down the conversation.

What to do instead:

- Wait. Give them a few extra seconds to find the words.

- Prompt with hints in Shona, or refer back to words and phrases from stories you’ve shared.

4. Overloading With Grammar

It’s tempting to teach ‘the right way’ from the start — full grammar explanations, rules, and exceptions. But too much too soon can overwhelm and intimidate learners.

Imagine trying to speak while constantly running a mental grammar checker in your head. It’s exhausting.

Stories solve part of this problem because they introduce grammar naturally. A child might not know the grammatical term for the way a verb changes — but if they hear it over and over in a story, they start using it correctly without having to memorise a rule first.

What to do instead:

- Focus on phrases and patterns they can use right away.

- Introduce grammar gradually, and always tie it to real examples — stories are rich with those examples.

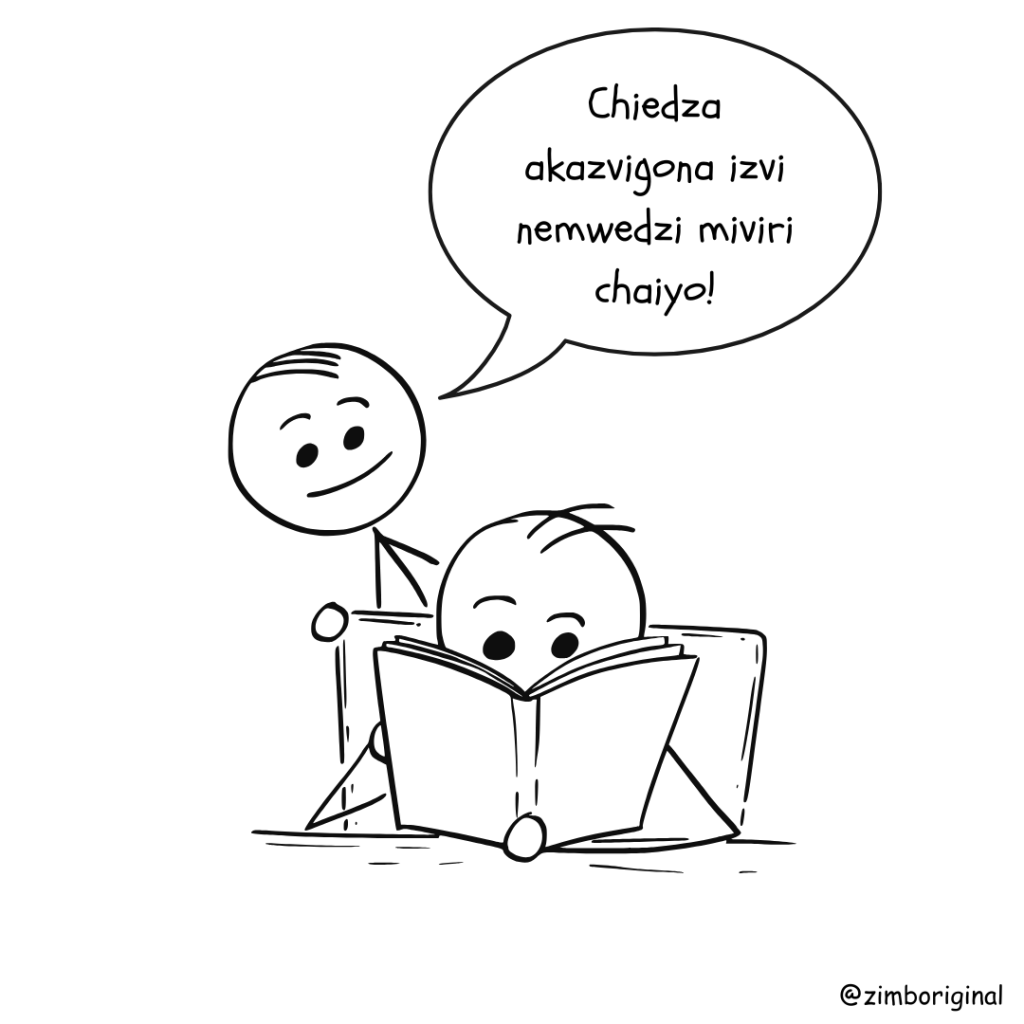

5. Inadvertently Applauding Poor Performance

Sometimes the slowdown doesn’t come from teasing — it comes from indifference disguised as pride.

A child might perform poorly in Shona, only to overhear a parent telling someone else about it with a chuckle, as if proud that their child struggles with the language. Over time, the child realises — even if no one says it outright — that in their parent’s heart of hearts, the language doesn’t matter.

It can also show up when parents rebuke poor grades in other subjects, yet completely ignore poor performance in Shona. The unspoken message is clear: ‘This subject isn’t important.’ And children pick up on those messages fast.

What to do instead:

- Take Shona results as seriously as other subjects.

- Show genuine interest in the learner’s progress, even if it’s small.

- Celebrate effort, not just grades. Stories can be a great way to encourage practice — ‘Let’s read this one together and see if you can spot three words you know.’

6. Comparing Learners to Others

‘I know someone who learned Shona in three months!’

Comments like this might sound encouraging, but they often backfire. Everyone’s pace is different — comparing can make learners feel slow or ‘not good enough.’

What to do instead:

- Compare the learner only to their past self. ‘Last month you didn’t know that word — now you’re using it naturally!’

- Make progress personal, not competitive.

- Use stories as a way to mark growth — re-read an old favourite and notice how much more they understand now.

7. Over-Correcting Every Sentence

Correction is important, but if it happens constantly, learners can feel like every sentence they speak is ‘wrong.’ They start focusing more on avoiding mistakes than on communicating.

What to do instead:

- Pick your battles. If the mistake doesn’t block understanding, sometimes it’s best to let it slide for now.

- Focus on one or two corrections per conversation.

- Use stories to reinforce correct language — hearing it naturally repeated is often more effective than immediate correction.

Final Thoughts

If you’re around someone learning Shona, you have more influence than you think. You can either be the wind in their sails or the invisible weight slowing them down.

Stories are one of the gentlest yet most powerful ways to give learners that wind. They don’t just teach words — they connect the language to emotions, humour, culture, and memory. That’s why the Zimboriginal children’s library exists: to give young learners a fun, pressure-free way to live in the language, one story at a time.

Encourage mistakes, keep speaking Shona, read together, and give them the space — and patience — to find their words. A safe, story-rich environment isn’t just ‘nice to have’ — it’s the fastest way to turn learners into confident speakers.