This post was last updated on 28 August 2025.

Culture and language are inextricably intertwined. Over the past few years, I’ve spent considerable time researching and writing about Shona culture, customs, and everyday life. Naturally, this led me to study the Shona language as well. Many people are surprised when I tell them this — after all, I have no formal training in language studies. But I believe that what one studied is far less important than what those studies empower one to do. For me, my work allows me to explore my interests while also helping others, particularly children learning Shona.

When I first began helping a few learners, I admit I felt a bit overwhelmed. I wasn’t sure what approach would work best and wanted to avoid replicating a classroom-style method that might feel dry or disconnected from real life. Through research, experimentation, and hands-on experience, I gradually discovered a set of strategies that form a structured yet intuitive approach to teaching Shona. The Covid-19 pandemic also pushed me to explore virtual learning, which helped me manage logistical challenges and rethink the way language could be taught.

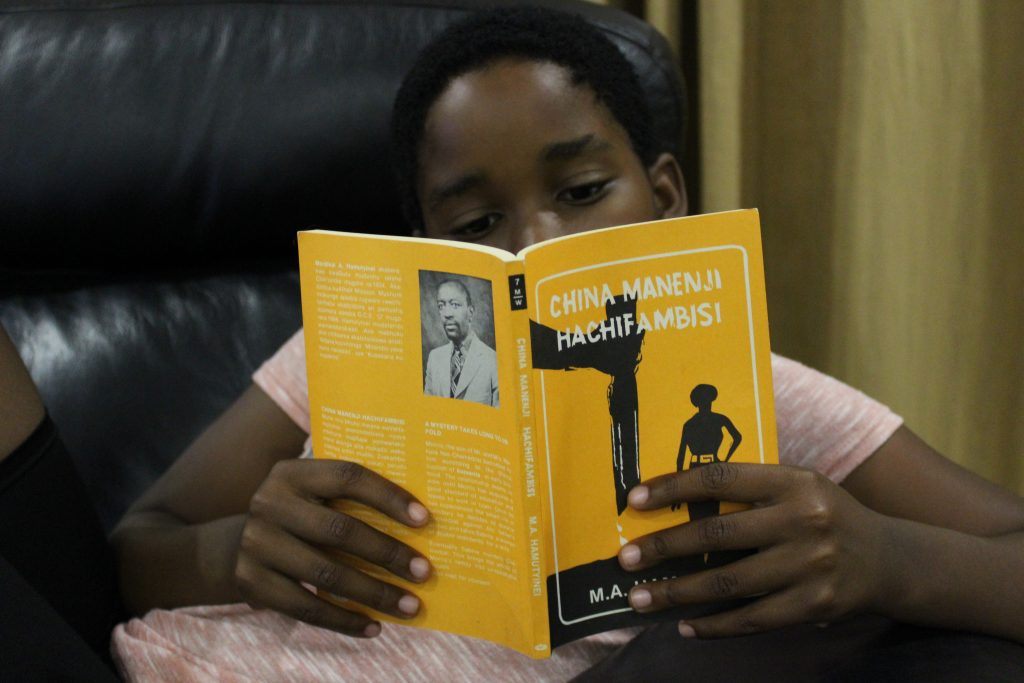

Much of my current teaching revolves around my digital Shona story library, a growing collection of stories at different levels designed to build skills gradually and contextually. Through this library, I’ve found a way to make language learning engaging, culturally rich, and relevant to the child’s everyday world.

After reflecting on what works best, I’ve distilled my approach into five key ingredients:

1. Covering All Four Skills: Reading, Writing, Listening, and Speaking

Language is not just about knowing words or grammar rules; it’s about using those words to communicate meaningfully. To develop true ability, children need to practice all four core skills: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. The story library allows this in a seamless way.

Reading

Illustrated stories let children follow along, connecting words to images and context. Reading helps build vocabulary naturally, and seeing the language in use strengthens comprehension.

Writing

Learners practice retelling stories, summarizing them, or completing story-based activities in writing. These exercises reinforce grammar and sentence structure while giving children a tangible sense of accomplishment.

Listening

Stories read aloud allow children to hear correct pronunciation, rhythm, and intonation. Listening also helps them internalize sentence patterns and vocabulary before they try to produce them.

Speaking

Discussion questions, role-play, and storytelling activities encourage learners to speak, express opinions, and narrate events. By speaking about familiar stories, children gain confidence in using Shona in real-life situations.

For example, a story about a child helping a neighbor carry water can become a discussion activity. The child might narrate the events in their own words, ask questions about the story, or describe similar events from their own life. This way, all four skills are practiced in an integrated, natural manner.

2. Culture-rich content

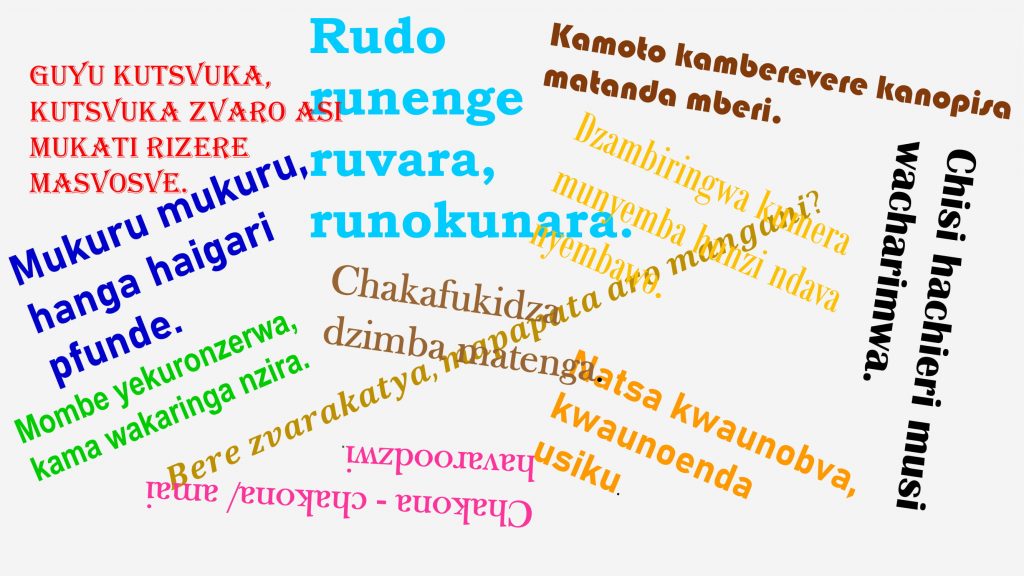

It is commonly said that language learners are also culture learners. A language is naturally related to or associated with a certain culture. An article I wrote titled ‘Should children maintain their native language?’ raises some interesting arguments about the relationship between culture and language. Incorporating culture-related content in language learning is relevant in instances where it provides context for the origins and uses of certain words and expressions. For instance, many people will have challenges understanding many Shona proverbs until they have some knowledge of the context in which these proverbs originated.

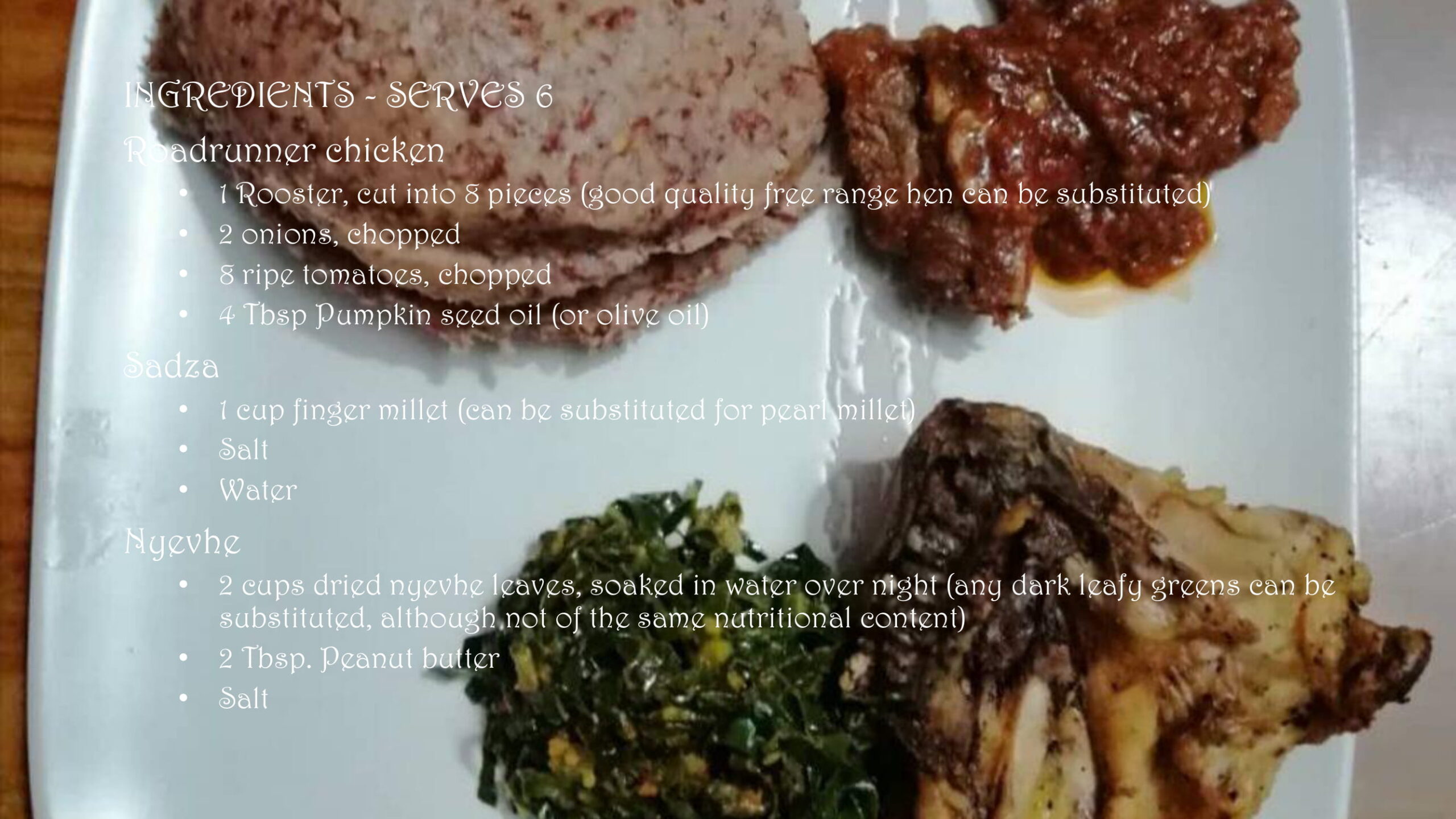

The stories in the library present a mix of cultures, but I ensure that Shona culture is well represented. This cultural dimension transforms language learning into a journey of understanding the worldview behind the words. For example, one story focuses on a little boy who is nervous about performing a traditional dance in front of his entire village during a special celebration. Children not only learn new words, but also gain insight into Shona dances, festivals, and customs.

Similarly, analyzing language reveals culture. In another article, 6 things I have learned through analysing over 200 Shona proverbs, I explore how proverbs serve as a rich repository of indigenous knowledge, reinforcing the idea that language learning is also cultural learning.

3. Story-based tasks

I learned about the task-based learning approach when I took a course on Teaching Reading. Thanks to MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). Tasks relate to solving a problem in the real world. The goal is to produce a non-linguistic outcome, so a focus on meaning rather than form is primary.

Tasks act as “mini-projects” that reinforce comprehension, vocabulary, and grammar while keeping the focus on communication. They encourage problem-solving and critical thinking within the context of language learning. Children experience language in action — seeing it as a tool rather than a set of rules to memorize.

One of the advantages of this approach is that it mirrors real-life communication. Children learn that Shona is a living language used to express ideas, ask questions, solve problems, and tell stories — not just a subject to pass in school. Some tasks even involve learners communicating with other children around the world, offering exposure to diverse perspectives and practical language use.

4. Vocabulary in context

Vocabulary is the backbone of language learning. The challenge is that memorizing lists of words without context rarely leads to fluency. That’s where the story library comes in. Every story is a source of new vocabulary, showing children how words are used in context.

For example, the word ‘kubika‘ (to cook) appears in a story about preparing food. Children see it, hear it, write it, and even act it out. They learn not just the meaning, but also pronunciation, usage, and related expressions. Over time, the most frequent words naturally become second nature, forming a strong foundation for further learning.

This method also allows children to encounter words repeatedly in different stories and contexts, which strengthens retention. Instead of isolated memorization, vocabulary becomes part of a living, meaningful experience.

5. Focus on communication

Traditional approaches to language teaching often emphasize rules and sequences: learn nouns this week, prefixes next, verbs after that. While efficient, this approach rarely reflects how people actually use language in real life. Learning becomes about passing tests rather than communicating meaning.

By contrast, my approach emphasizes communication and understanding first. Stories provide context, and tasks allow learners to use words and structures as they naturally appear. Grammar and syntax are learned incidentally, as children try to convey meaning, describe events, or discuss a story’s ending.

For instance, a story about a child helping a sick neighbor might prompt learners to describe what happened, ask questions, or predict what could happen next. Grammar rules are introduced as they arise in context, making them easier to understand and apply.

This focus ensures that learning Shona is not just academic. Children are able to use the language meaningfully, in ways that connect to their lives, their families, and their communities.

Final thoughts

Putting it all together, these five ingredients — covering all four skills, culture-rich content, story-based tasks, vocabulary in context, and a focus on communication — create a holistic approach to Shona language learning. With every story added to the library, children gain new opportunities to engage, reflect, and practice, making learning both effective and enjoyable.

As I continue to work with learners and expand the library, I see more ways to connect language learning to real life and culture. The journey is ongoing, and the proof, as they say, is in the pudding: children who engage with these stories grow not only in language skill but also in confidence, curiosity, and cultural understanding.

The above are my personal views and given in no professional or expert capacity. If you think I can help, feel free to reach me on shungu@zimboriginal.com.

Hey matanga chinhu chakakosha. Asi madii kuzviita nemitauro yeZimbabwe. Kana zvichisandurwa zvoitwa nerurimi rwakasiyana kuti vamwewo vanzwe pane kuzvinyora nechirungu. Ndofunga hapangashayi vangade kupota vachibatsira kuturikira nemitauro yemuno.

Ndaongoda kuti ndipewo zano. Asi ndinomutenda nebasa guru iro matanga. Tichabatana tipane matma. Wakuru wakati, ‘Zvikomo zvingopana mhute’.

Tinotenda nemashoko enyu anokurudzira. Ndinogamuchira nekudzamisa pfungwa pese ndinopiwa mazano nevamwe; vakuru vakati ‘mazano marairanwa, zanondoga wakapisa jira.’ Ndinovimba kuti nerimwe zuva zimboriginal ichakwanisa kupa ruzivo ichishandisa mitauro mizhinji yomuZimbabwe.

This is so amazing.please notify me with knew information l am learning to be a shona teacher

Thank you Kelvin. Will certainly share new posts; I have added you to my newsletter mailing list.