Spirits, Shona religion, and culture

Spirits are an important part of Shona religion and traditional beliefs. In Shona understanding, the spiritual world connects directly to daily life, influencing how people live, work, and interact. People often interpret illness, leadership, talent, rain, family well-being, and community harmony through spiritual influence.

While all Shona spirits share one thing in common, that they can appear through human hosts, they are not all the same. Each spirit has its own origin, purpose, and relationship with people, families, or communities.

Spirits usually communicate through a medium, known in Shona as a svikiro. Sometimes, a person only realises they might be a svikiro after a serious illness that medicine cannot cure. Alternatively, there could be other signs such as unusual life events, recurring dreams, ongoing misfortune, or patterns like difficulty getting married. When these signs appear, people seek guidance from the spiritual world.

A traditional healer, called a n’anga, identifies the spirit involved and recommends what should be done. This may include a ceremony to formally welcome and ordain the spirit with a libation, or rituals to remove a spirit that is causing harm.

In this post, we look at six types of spirits recognised in Shona religion and culture.

1. Mudzimu

Ancestral spirit

Mudzimu is an ancestral spirit.

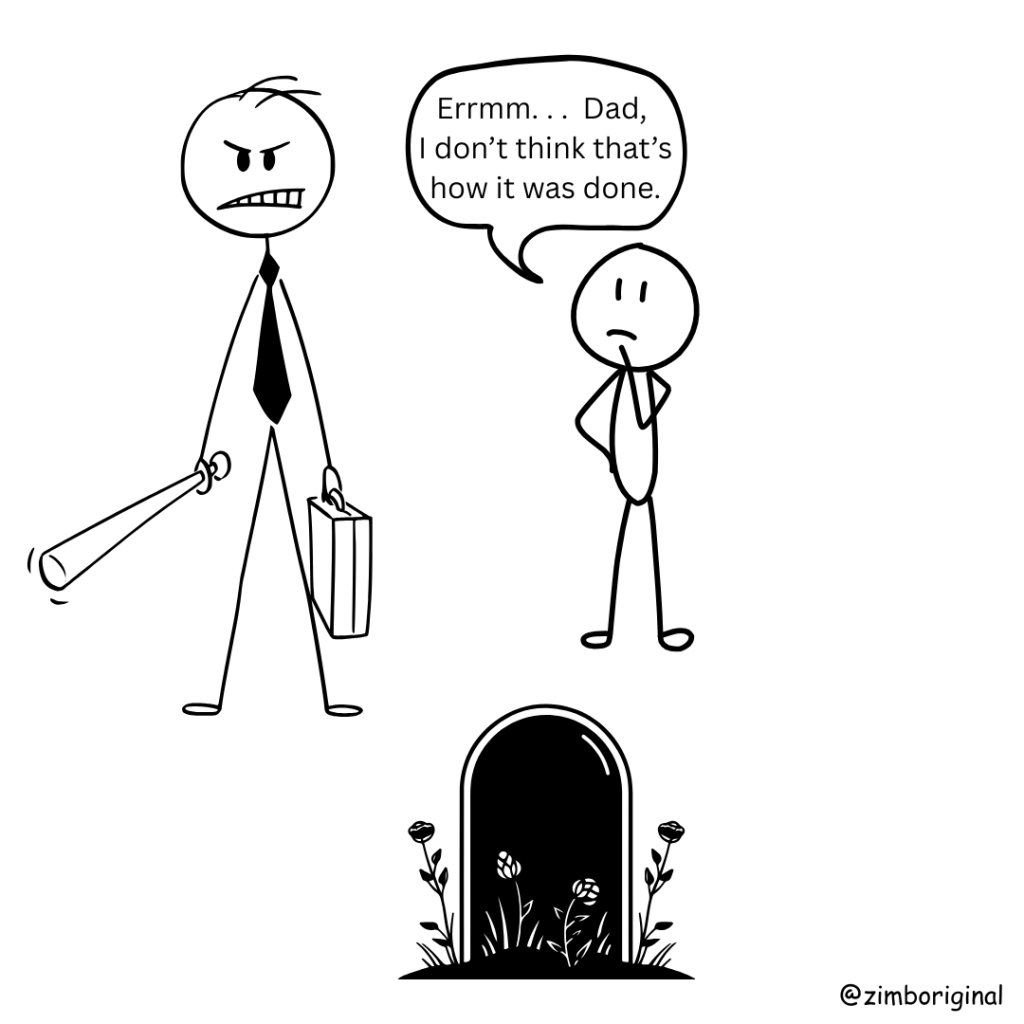

Ancestors are family elders, those in your family line who lived before you, especially those preceding your grandparents. In Shona belief, when a person dies, their spirit does not immediately become an ancestral spirit. Instead, it wanders until it is ritually invited to return and protect its descendants.

This invitation takes place through a ceremony known as kurova guva. During this ritual, the spirit is formally incorporated into the ancestral lineage. It then becomes a mudzimu and joins the madzitateguru (ancestral elders) in nyikadzimu, the spiritual realm of ancestors.

Once recognised, vadzimu (plural of mudzimu) have two main responsibilities:

- Protecting their descendants from harm and misfortune

- Providing guidance and revelation on various aspects of life, including family matters, personal decisions, and the well-being of household members

They may communicate through dreams, visions, illness, or possession of a svikiro. Unlike other spirits, a mudzimu is specifically tied to a family lineage.

2. Gombwe

Regional guardian spirit

Gombwe is a regional or territorial spirit.

Unlike a mudzimu, a gombwe is not an ancestral spirit. It is believed to come from the Supreme Being and serves as a link between the people and the divine. A gombwe is connected to a tribe or a particular region, not to a single family.

The main responsibilities of a gombwe include:

- Bringing rain and ensuring good harvests

- Protecting the land and its people

- Safeguarding the welfare of the region as a whole

A gombwe speaks on matters that affect everyone, such as drought, war, disease, or other crises that concern the entire community.

It is not unusual for a gombwe to possess someone who is already a medium of another spirit. In such cases, the gombwe may overshadow the other spirits while it is active.

The same gombwe spirit may possess different people at different times. Even though it is understood to be the same spirit, it may express itself differently in each host. Its tone, manner of speaking, or focus may vary depending on the person and the situation. This is one reason why people sometimes find it difficult to distinguish clearly between spirits and their roles.

A well-known example often associated with a powerful territorial spirit is the spirit of Mbuya Nehanda, remembered in Zimbabwean history for its guidance during resistance against colonial rule.

3. Mhondoro

Clan Spirit

A mhondoro is a clan spirit, often linked to the founding ancestor of a clan or to a ruler.

While it belongs to the wider category of ancestral spirits, it is different from the ordinary family mudzimu. A mudzimu protects one family. A mhondoro protects an entire clan, which is a group of related families or villages who share ancestry and territory.

The word mhondoro also means ‘lion,’ and this connection is important. Traditional accounts describe royal burial practices in which the internal organs of a deceased king were placed in a clay pot. It was believed that as the organs decayed, maggots would form, and from this decay lions would eventually emerge. These lions were understood to become hosts of the king’s spirit. In time, the spirit could then leave the lion and choose a human medium. This belief strengthened the connection between kingship, lions, and clan guardianship.

The responsibilities of a mhondoro include:

- Protecting the clan and its territory

- Guiding and confirming leadership within the clan

- Providing direction during war or conflict

- Exercising spiritual authority over the land connected to that clan

Unlike a gombwe, which focuses on the wider region, a mhondoro is tied specifically to a clan and its ruling lineage. Matters of chiefly succession, territorial protection, and clan leadership are understood to fall under its guidance.

4. Shavi

Patronal spirit

A shavi is often described as a patronal or talent spirit.

The phrase kubuda ushavi refers to someone displaying extraordinary ability after being possessed by a spirit. Many believe that shavi possession can be a form of divine endowment, special talents granted by the Supreme Being. However, sometimes a shavi can be an inherited family spirit, passed down through generations. For example, shavi reuroyi may remain in a family and manifest in descendants.

Examples of abilities attributed to shavi possession include:

- Exceptional hunting skills

- Artistic or sculpting talent

- Musical ability

- Healing powers

Not all mashavi are considered positive. Some may confer traits that are harmful or frowned upon by society, such as witchcraft, theft, or other antisocial behaviour.

Common types of mashavi include:

- Shavi redona: Traditionally associated with women. Those possessed by this spirit are said to have an extreme focus on physical cleanliness and may find sexual activity repulsive.

- Shavi reuroyi: A family or inherited spirit associated with witchcraft or harmful magical abilities.

Almost anyone can be possessed by a shavi, though the intensity varies. In those who have experience as mediums, possession may appear strong and obvious. In others, it may be more subtle, only noticeable through unusual behaviour, talent, or abilities.

When shavi possession is suspected, a traditional healer (n’anga) is consulted. A ceremony may then be held either to accept and formalise the spirit or to remove it. Ideally, a harmful shavi is rejected, but sometimes a spirit only reveals its true nature after it has already been accepted.

5. N’anga spirit

Healing and divining spirit

A n’anga is a traditional healer and diviner, possessed by a spirit of healing and divination. The possessing spirit is generally regarded as benevolent, guiding the n’anga to diagnose illness, prescribe herbal remedies, interpret spiritual causes of misfortune, and mediate between the living and the spiritual world.

Healing ability may be acquired in several ways:

- Through a shavi spirit

- Inherited from a family line of healers

- Through spiritual encounters with njuzu (water spirits)

- By direct spiritual calling, often revealed in dreams

Some individuals are believed to disappear into rivers or pools after encounters with njuzu, returning weeks or months later with healing powers. Others experience recurring dreams of water spirits, prompting them to consult a n’anga for guidance and ritual initiation.

There are also those who intentionally seek healing abilities, sometimes acquiring charms or medicines believed to grant such powers.

While the healing spirit is considered good, ethical questions arise when some healers agree to use their knowledge or medicines to harm others.

6. Muroyi spirit

Spirit of witchcraft

A muroyi is a person believed to inflict harm through witchcraft.

In Shona belief, this is associated with possession by an evil spirit. Like the n’anga spirit, it may originate from a shavi or be inherited through a family line.

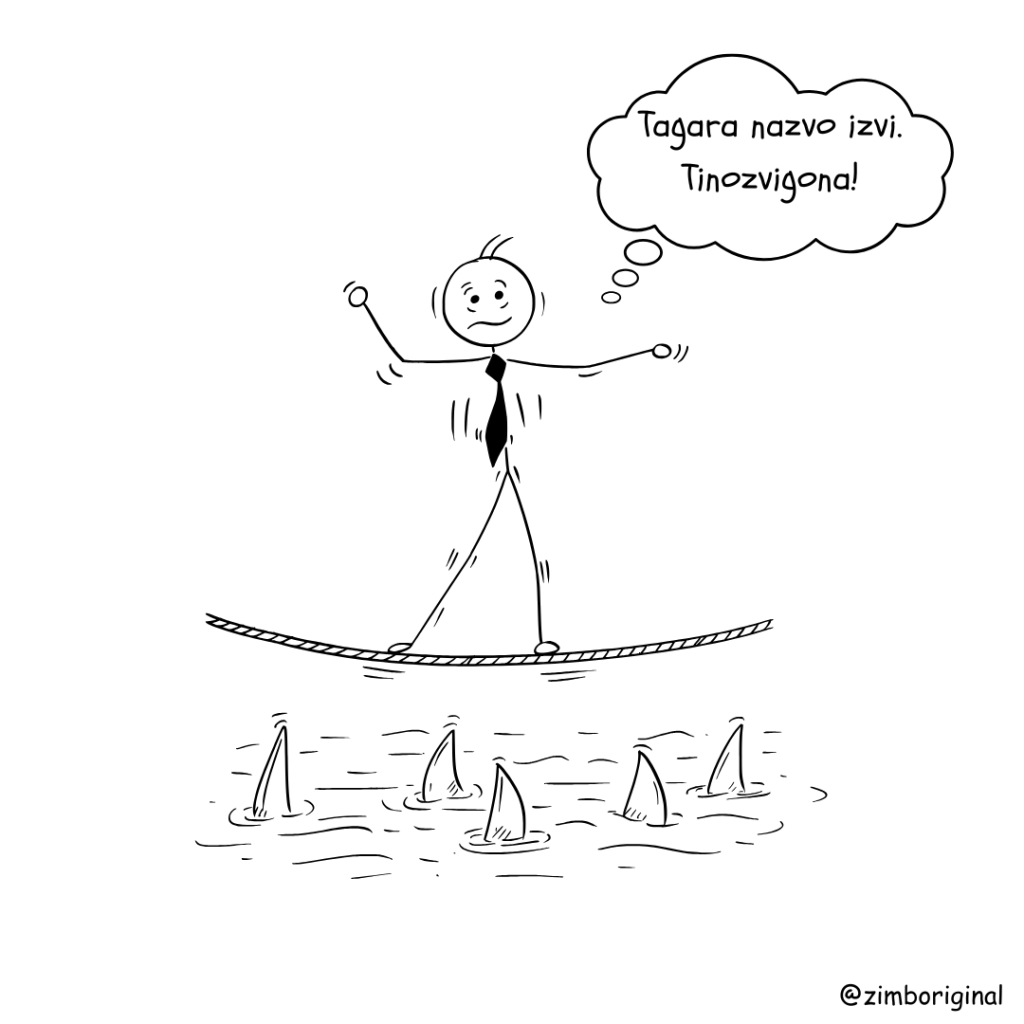

Witchcraft spirits are often thought to pass from one generation to another. A person may carry such a spirit unknowingly, while in other cases, an individual may become aware that the spirit is attempting to take possession.

When this happens, some attempt to rid themselves of the spirit through ritual intervention. However, it is widely believed that rejecting a witchcraft spirit may require immense sacrifice. As a result, many are said to accept possession rather than risk the consequences of resistance.

Understanding Shona spirits isn’t always straightforward

Shona religion is deeply tied to everyday life, yet there are grey areas that make interpretation challenging.

A single person may host multiple spirits simultaneously. For example, one could be the medium of a clan mhondoro, and a gombwe. Distinguishing which spirit is acting at any given time can be difficult.

Historical records also pose challenges. Shona religion was widely practiced before Christianity, but much of its original practice was disrupted. Our understanding today comes from oral accounts passed down by those who experienced it, many of whom where minors at the time. Also available are written accounts from early white historians, whose interpretations may have been incomplete or biased.

Despite these complexities, learning about Shona spirits offers valuable insights into how the Shona people understand life, ancestry, and their spiritual world. Studying these spirits helps us appreciate the beliefs, values, and practices that continue to shape Shona culture today.

Note of thanks

I would like to express my gratitude to the researchers, creators, and scholars whose work informed this post. Special thanks to M. Gelfand (The Shona Religion), Gombe J. M. (1998, Tsika DzaVaShona), ZimbOriginal (2019, 5 Death Premonitions – Spirits, the Afterlife and Indigenous Religion in Zimbabwe), and Takawira Kazembe, Ph.D. (“Divine Angels” and Vadzimu in Shona Religion, Zimbabwe). Their research and insights have been invaluable in helping to understand Shona spirituality, culture, and traditional practices.