When I started helping children learn Shona around 2019, I have to be honest—I was anxious, but I thought it couldn’t be that difficult. After all, I was just helping children with Shona in the ways I imagined, right? But as I met more learners and worked closely with them, I quickly realized the challenge was far more complex than simply teaching words and grammar.

In this post, I share the lessons I have learned along the way and the personal growth I have experienced—insights that will be useful for anyone learning Shona.

Worried Your Child Isn’t Ready for the Grade 7 Shona Exam?

Get ahead now — join our January 2026 revision program waitlist.

Lesson 1: Immersion is key – you can’t learn without using the language

When we learn our first language as children, we are completely immersed in it. We hear it, speak it, and live it long before we even realize we are “learning.” In that process, even the people around us are teaching without trying.

For older learners, however, the approach is often very different. Many think that studying a language like math or science—through vocabulary lists and grammar rules—is enough. It isn’t. Languages live in conversation. To truly learn, you must speak, listen, and use the language daily.

I saw this firsthand with my students. No matter how committed they were to memorizing words or completing grammar exercises, something was missing. They weren’t using the language in their everyday lives—and without that, progress stalled.

Lesson 2: Create a Shona-rich environment if it’s not naturally spoken at home

Growing up, my parents couldn’t sustain an English conversation for even five minutes. Shona was the air we breathed. It surrounded us in every interaction, in every story, in every daily task.

Today, many Zimbabwean parents—including those of my generation—can carry on entire conversations in English without switching once to Shona. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing for bilingualism, but it does mean that Shona often loses its natural place in a child’s life.

If Shona isn’t naturally used at home, parents need to actively find ways to immerse their children in the language. Without that exposure, children may never develop the same comfort and intuition in Shona that they do in English.

How I have tried to bridge the gap

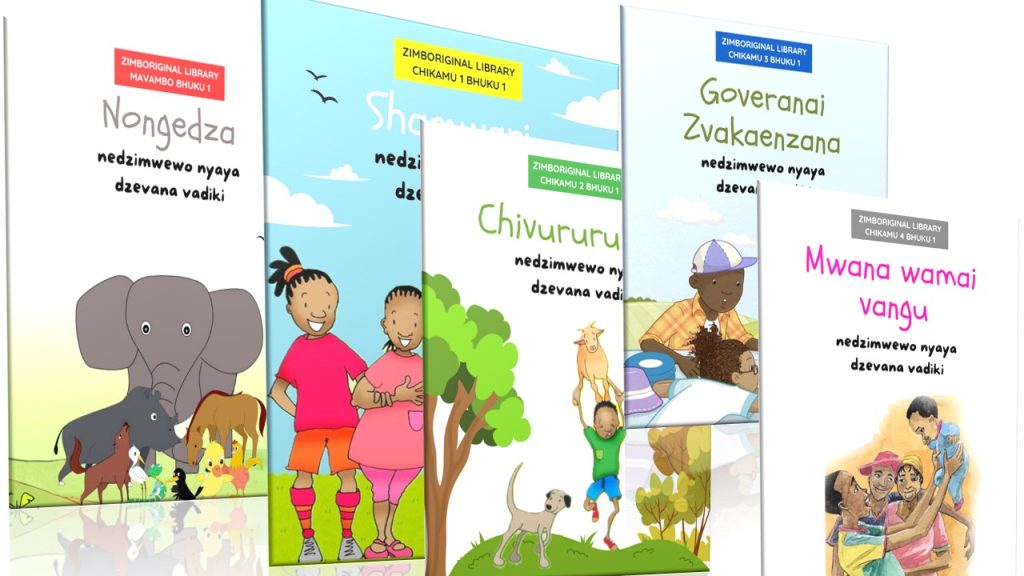

I knew I couldn’t be in my learners’ homes, making sure they spoke Shona every day. But I could find another way to bridge the gap. I decided to create a digital library of beautiful children’s stories in both Shona and English—something learners could access anytime, anywhere.

In addition to the digital library, I also produced four printed Shona titles. These resources give children the chance to immerse themselves in the language, explore stories, and experience Shona in a way that feels natural and enjoyable.

Every story read, every Shona word encountered, helps learners internalize the language. The work continues, and with each story, I hope to see a generation growing up with Shona as a living, vibrant part of their daily lives.

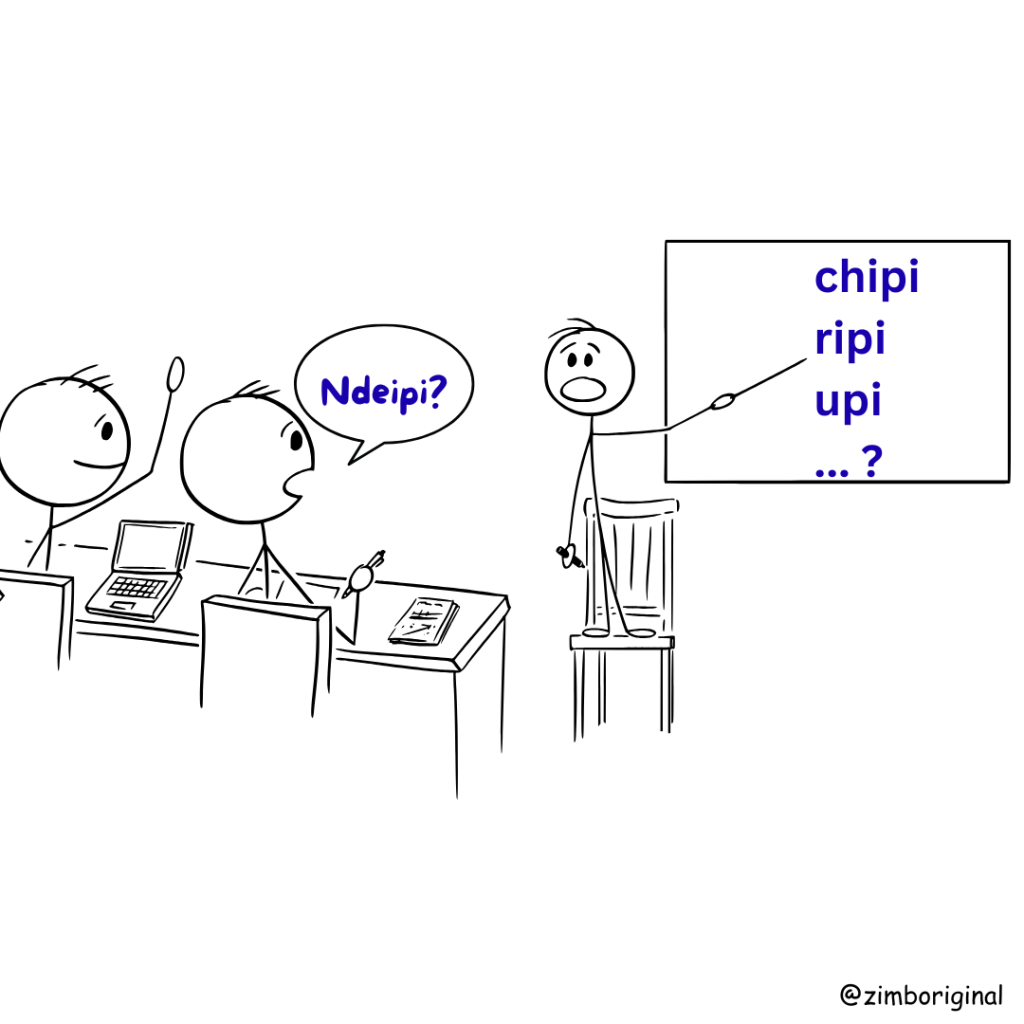

Lesson 3: We can’t wait for schools to do it for us

Shona faces significant challenges today. It often gets just one period a week in schools. Supplemental resources are limited. Piracy discourages publishers from producing new Shona books. Writers have little incentive to create because the market is small and poorly funded. Government spending on educational materials has shifted, leaving even fewer resources for non-core subjects.

These challenges don’t just affect language skills—they also weaken the bonds of heritage, identity, and cultural pride. Societies that value their language and culture are better positioned to thrive economically, socially, and politically.

Champions matter

When institutions struggle to carry this responsibility, the duty falls to individuals. We need champions for Shona—people who keep the language alive, promote cultural pride, and fill the gaps left by schools and publishers. Champions are not passive supporters; they are drivers of change. They create opportunities to use Shona, encourage others to speak it, and demonstrate its value. These champions can be parents, teachers, community leaders, or even older siblings.

The lesson is clear: we cannot wait for schools, publishers, or government programs to preserve and promote Shona. It is up to us—parents, learners, and communities—to create opportunities, share resources, and be the change we want to see.

Lesson 4: Family is at the heart of learning

If schools aren’t stepping up, the strongest force for Shona learning lies at home. Children learn a language best when it’s part of everyday life—spoken at the dinner table, in bedtime stories, during games, and in conversations with grandparents.

Extended family members play a vital role too. Storytelling, singing traditional songs, or sharing proverbs in Shona builds a living connection to culture that no textbook can match. Families are the everyday champions of the language, shaping both skills and cultural pride through consistent, lived experience.

Lesson 5. Technology can help too

While some schools resist digital learning, technology is one of the most powerful tools we have for keeping Shona relevant. Audio stories, mobile apps, and online communities make it possible for learners anywhere in the world to stay connected to the language.

That’s one of the reasons I created ZimbOriginal’s learning site – which includes the digital story library that supports the Shona learning program. Learning a language through stories exposes learners to much more vocabulary than drills and flashcards could ever achieve, without waiting for a weekly lesson at school. By using these resources, families can reinforce learning at home naturally, without pressure, while still fostering pride and fluency in the language.

Lesson 6: We can change how we see Shona

One of the biggest challenges isn’t just time or resources—it’s attitude. In many communities, English is seen as the language of success, while Shona is often viewed as inferior or inadequate. But if we do not use Shona, how can it improve? Its strength comes through use, and we are the ones who can make it thrive.

Negative perceptions lead learners and parents to see Shona as less valuable, resulting in less practice and gradual language loss. Changing this mindset is as important as teaching the language itself, because valuing Shona is the first step toward keeping it alive and relevant.

We all have a role to play

Shona won’t survive on school timetables alone. It needs to live in homes, communities, and hearts. Whether you’re a parent, educator, or simply someone who loves the language, you have the power to keep it alive.

We all have a part to play—by speaking Shona daily, encouraging its use in meaningful ways, and passing on its stories and wisdom to the next generation.

And if you’re looking for a way to start, explore the stories and resources we’ve created at Zimboriginal. Because every conversation, every story, and every champion counts in keeping Shona strong.