The Shona trace a person’s descent through the paternal line

In Shona society, a person’s descent is traced through the paternal line. This means both males and females identify their bloodline (rudzi) by tracing their roots through the males. So, only the males will continue to pass their family identity to their children. Because of this, a mother is considered to be a ‘non-relative,’ (mutorwa).

This kinship structure should, ideally, be identified through relatives with a common surname. It is however quite common for some Shona people to bear the surname of their mother for various reasons including that a man would have refused to take responsibility for his child. Where a mother’s surname is adopted, the paternal line could potentially be distorted.

Ukama is the Shona word for ‘relationship/s.’ The way relationships are defined or understood depends on who the relative (hama) is. The below rules to help one understand relationships are based on the patrilineal kinship structure described above.

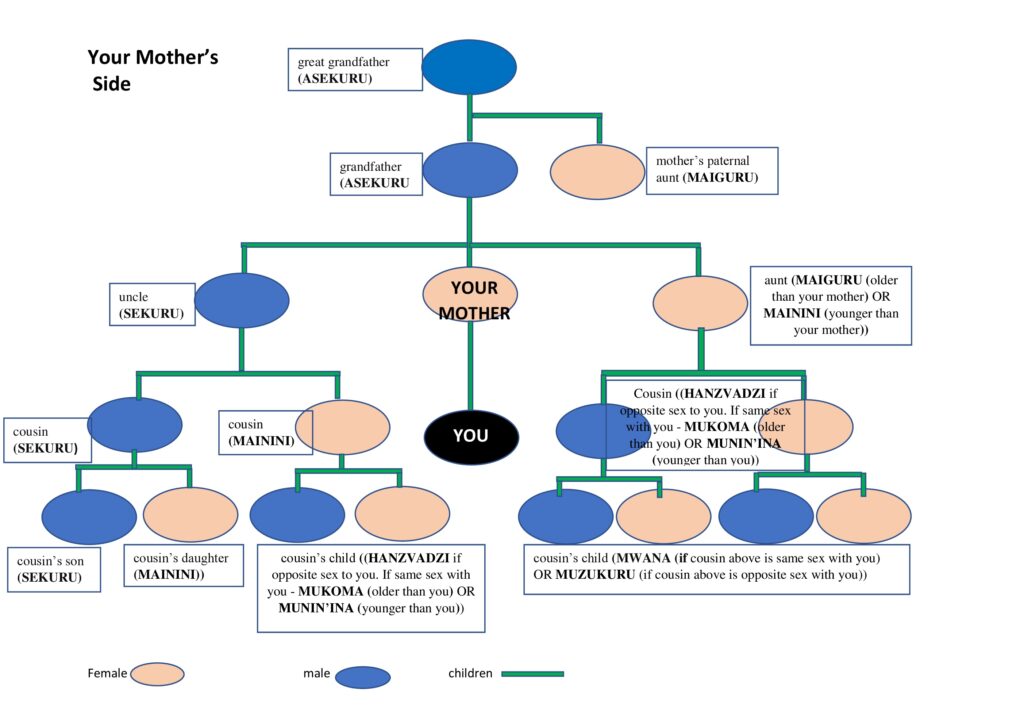

RULE #1: Any man of your mother’s patrilineage is your sekuru, and daughters born to him are your ‘mother’

Strictly adhering to the general surname protocol whereby a child adopts the surname of the father; this rule would apply to all relatives from your mother’s side with whom she shares a surname. You would consider all the women to be a mother to you. Those older than your mother would be maiguru and those younger than her, mainini. While the grandfather rightly is asekuru, the lineage of sons from this side of your family – uncles, their sons, and sons of their sons are also termed sekuru (variation to asekuru which I prefer to use for those other than the grandfather).

Uzukuru

To your mother’s family, you are a muzukuru, recognizing the ‘fathers’ – the clan, that begot your mother. As described above, the grandfather, his sons, and sons of his sons are all recognized as sekuru. This relationship of being a muzukuru (uzukuru) is an interesting and important aspect of Shona family ties. It however mostly plays out between sekuru and his nephews rather than nieces. Perhaps this is related to the patrilineal kinship structure, as at some point women will be exported to other lineages through marriage. Sekuru and muzukuru have a very close relationship and can confide in each other. This relationship also allows muzukuru to tease, criticize and openly air his views unreservedly to sekuru and his family. In addition, the relationship between muzukuru and sekuru’s wife, who is a muramu to muzukuru, is generally free and easy.

There also exist ceremonial duties reserved for muzukuru. During family gatherings such as funerals, the presiding role is performed by muzukuru. This presiding official is known in Shona as dunzvi. At inheritance ceremonies, the muzukuru is also the presiding official known in this case as chigadzanhaka.

Trying to understand the concept of uzukuru can be both confusing and overwhelming. Firstly, from your mother’s side of the family, you are identified as muzukuru by her father and her brothers. From your father’s side, you are identified as muzukuru by your grandfather and your father’s sisters. Secondly, there will be preceding and succeeding generations of vazukuru such that it becomes difficult to grasp it all. There would be you and the children of your mother’s sisters as vazukuru; then there would be children of the generations of women before and after your mother.

RULE #2: In your patrilineage, members of the first generation above you, are your ‘fathers’. Those of the first generation below you, are your children. Members in your own generation are your brothers and sisters.

Unlike your mother’s side of the family, in which you are a muzukuru, your father’s side is the clan to which you belong. An uncle is babamukuru (older than your father) or babamudiki (younger than your father). Your paternal aunts, being of the same ‘blood’ as you are in essence your father and referred to as atete. A brother or sister of the same sex is either mukoma if older than you or munin’ina if younger. If of the opposite sex, the term used is hanzvadzi and no distinction is made between older or younger. This is because a man, being a father in the clan, automatically assumes seniority.

In her clan, a woman would be generally empowered as opposed to when she sits as a member of her husband’s family. She can openly speak out, advise or preside over family court sessions. However, authority generally rests with the men such that young boys can perform traditional roles required of the father.

The curious case of atete and muzukuru

While clan members of the first descending generation would be your children, it is common for a woman to refer to a brother’s child as muzukuru instead. This could be considered somewhat misplaced as atete is a father. In a woman’s absence, the daughter of her brother could perform ceremonial roles on her behalf. Traditionally, this included her even becoming a substitute wife after the death of atete. Such a woman given as a substitute wife to a widower is called chigadzamapfihwa. It is possible that this custom is still practised today, though to a lesser extent.

According to J.F. Holleman 1969, the Hera used mwana as the term for which a woman referred to her brother’s child, while all other tribes used muzukuru. Mwana is easily understood and agreed with. It is in line with the principles of Shona family ties, as atete is a father. The usage of muzukuru for brother’s child is thought to have been an attempt to imitate the reciprocity of the term hanzvadzi which means both brother’s sister and sister’s brother.

RULE #3: A woman’s husband regards all males of her patrilineage as ‘fathers-in-law.’ At the same time, all the females are placed in a similar position as his wife and become his ‘wife.’

A man accords a high level of respect to the family of his wife. The brother of his wife is a tezvara and commonly addressed as tsano. This applies to all males in his wife’s patrilineage. This level of respect also ensures that he keeps a social distance from tsano’s wife, whom he relates to in the same manner he does with the mother of his wife. For other members of the family in generations other than that of his wife, the specific terms he uses to address them are similar to those used by his wife. While he would refer to her father and mother as tezvara and ambuya; he would directly address them as his wife does – baba and amai.

The wife’s older sister is referred to as maiguru and the younger one as mainini. He would regard his wife’s atete as if she was an older sister, and as such could alternatively address her as maiguru. In the same manner, the daughter of his wife’s brother would be mainini. This, as already mentioned earlier, highlights the anomaly in atete using the term muzukuru to refer to her brother’s daughter. To maiguru, a high level of respect is given. With an unmarried mainini however, the relationship could be a lot more friendly and playful because of uramu.

Uramu

A man and his wife’s sister regard each other as muramu. Muramu is one who can be identified as a potential wife or husband. Uramu (the relationship around this potential for marriage) exists between a man and the females of his own wife’s lineage, and in the other instance between a man and the females of the lineage of his brother’s wife. The relationship of uramu is one of familiarity and generally gives a man the right to play with the unmarried younger sisters of his wife or the wives of his younger brothers. It could potentially be disruptive, as it is common that sexual relations do happen with minimal disapproval from elders in the family.

RULE #4: For the family of a woman’s husband, she would generally address all but his brothers and sisters, as he would.

A woman married into a family is a muroora. She is generally expected to show respect, humility, and subservience to her in-laws. While she could have a more relaxed relationship with the younger brother of her husband, she would show a greater level of respect for his older brother and regard him as she would his father. Uramu also plays out, as described above. The way she would address her husband’s brothers is the same as her children would, distinguishing between older (babamukuru) and younger (babamudiki).

RULE #5: For relationships based on clans as identified by totems (mitupo), apply rules 1 to 4.

According to the totemic system used by the Shona, clans are identified by mitupo (totem) and zvidawo (sub-clan names/ praise names). A number of these sub-clans may be linked to a single clan. Given this, the chidawo is the distinguishing feature of a clan. A child gets the mutupo and chidawo of the father and people of the same mutupo and chidawo claim a common origin; they are of the same rudzi. Among the Shona, the chidawo is often used to address and greet one another. Quite often, when people make acquaintance, they are interested in knowing the other’s clan. That way people get to identify their ‘non-relative relatives,’ among other things.

Those of the same clan as one’s mother would be identified as a mother or sekuru. If of the same patrilineage, one could be identified as a father, brother, sister or child. Clans of in-laws could also be considered and terms of reference used accordingly.

Assigning a generation to the non-relative is normally done when applying this rule, whether by use of knowledge or judgment. That way, one can know which level of the hierarchy to use for the identification of an appropriate term of address. For example, one could be assigned to the first ascending generation as opposed to own generation.

The rules above are based on standardized Shona terms, or rather, those I am familiar with. With the various dialects of Shona, differences occur in the terminology used by the different tribal groups. In addition, there could be other family mixes that do not readily fit in the classifications above. For example, when a father remarries, the woman would be regarded as a mother and relationships defined accordingly. However, the extent of the relationship with this new mother’s family would most likely be limited or just a mere formality.

Understanding family ties and addressing relatives at family gatherings can sure be daunting given the intricate kinship organisation we use. I hope with the rules given in this article, you have a structured and memorable way to make it easier.

What do you call your wife’s sister’s husband?

Hi Thabani,

So your wife’s sister is maiguru or mainini depending on who is older. Their husband would be either babamukuru or babamudiki, to match what you call their wife.

Thanks for checking out my blog!

Cheers

Shungu

Thanks for your blog…What do you call my older brothers wifes brother?

Hi, my Zimbabwean friend tells me that his brothers wife is also his wife and that his brother and wife’s unborn baby would also be considered my friends baby is this correct?

Hi my girlfriend is from Zimbabwe and also said that her sisters husband can call my girlfriend as his wife I’m really confused and scared

Hi Yas,

That is correct. According to Shona tradition, there is potential for marriage between a man and the sister of his wife. However, unlike in olden times, inappropriate behaviour between a man and the sisters of his wife are becoming less common.

I’m Zimbabwean and even I get confused at who’s who’s sometimes. The post really helped.

Hi Michy T,

I’m glad to know this helped you! Thanks for stopping by.

Shungu

Hi, what does my wifes younger sister call me

Hi Cade,

Younger sister to your wife will call you babamukuru.

Thanks for checking out ZimbOriginal.

Cheers!

Hie, my only problem is when you call aunt (vatete) atete. In Karanga we say “Vatete” va shows some respect

Hi Godfree,

Interesting to know that ‘atete’ could be considered disrespectful. It is also not unusual for people to switch between the two, and even use ‘tete’ instead.

Thank you for checking out ZimbOriginal!

Hi

What do i call my husband’s sister (Vatete)’s husband?

In Shona culture, your husband’s sister is called vatete, and her husband is considered your mukuwasha. From his perspective, you are ambuya — a term that reflects the respect traditionally given to the wife of a man’s in-law (in this case, his wife’s brother).

So the relationship between you and your husband’s sister’s husband is that of mukuwasha and ambuya.

Hi.

Can I marry my brother’s wife’s sister?

Certainly. While it may be considered unusual, marrying into the same family as your brother is not forbidden in Shona culture. Any objections would likely come from the family level, not because the union is culturally taboo.