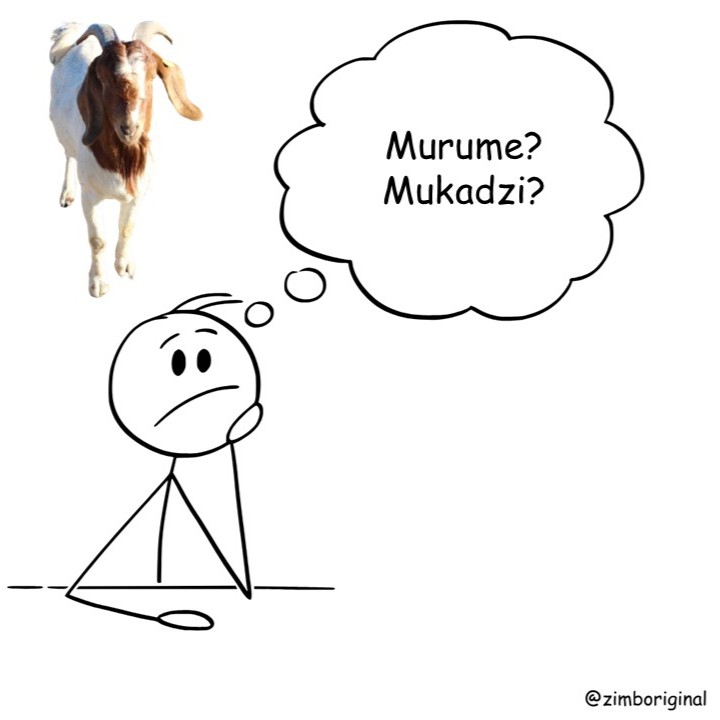

There’s a silly goat song we used to sing as kids:

‘Zvembudzi, zvembudzi, zvandikanganisa.

Murume ndebvu, mukadzi ndebvu!

Me-e! Zvandikanganisa!’

Loosely translated:

‘Goats, goats, you’ve completely confused me.

The man has a beard. The woman has a beard!

Bleat! I’m confused!’

And you’re probably wondering what this has to do with grammar. Well, every time I try to make sense of certain Shona grammar quirks, this song pops straight into my head.

You can support your child’s Shona learning journey with ZimbOriginal’s Shona Story library. Try it for FREE.

Shona grammar quirks

When teaching grammar, I’ve found that the easiest way to help learners is to spot patterns. Certain words trigger certain structures, and once you see the pattern, things start to make sense. But Shona also has many cases where the rules aren’t so clear-cut.

Over time, I’ve realised that the only way to master these is simply to notice and remember them. You learn to say, ‘Oh right, this is one of those tricky ones that works differently.‘ That ‘non-pattern pattern’ then becomes part of how you remember the grammar.

In this post, I’m going to share five of these unruly elements, so that next time you feel tongue-tied, all you have to remember is: ‘Ah yes, this is one of those.‘

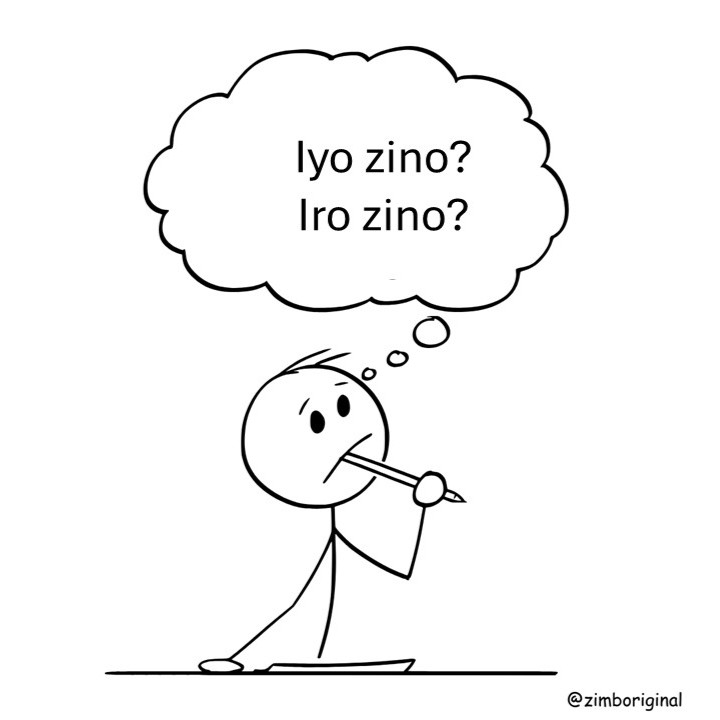

1. Words with the pronouns iro and iyo can be confusing

Without enough exposure, it’s hard to know how to form sentences for nouns that don’t take the usual prefixes found in most Shona words. With nouns that take prefixes like mu- or chi-, sentence construction is relatively straightforward.

Then come words with no clear noun prefix, such as shamwari, ziso, zino, mhuka, and mombe (as well as many animal names). This is where things get tricky, especially when forming plurals.

For some nouns, the plural is identical to the singular:

- shamwari

- mombe

- mhuka

For others, the plural is formed by adding the prefix ma-:

- ziso → maziso

- zino → mazino

These words, in their singular form, belong to different grammatical groups, taking either the pronoun iyo or iro. There’s no reliable way to predict which group a word belongs to. Words with iyo have a plural form identical to the singular, while those with iro take the prefix ma- in the plural. I’ve searched high and low for a clear rule explaining why this happens, but the reasoning isn’t immediately obvious.

Takeaway for learners:

- Notice which nouns use iro and which use iyo.

- Remember: nouns with iro take the prefix ma- in the plural, while nouns with iyo have the same form for singular and plural.

- With exposure, you’ll start to instinctively know the correct forms.

2. Action verbs are not all the same

As a lifelong Shona speaker, I only became aware of this when I started teaching. Because, honestly, I’ve hardly ever had to think first before speaking Shona.

Strictly speaking, a rule exists, but the challenge is first understanding whether a verb communicates a state or an action. Only with lots of experience does using certain verbs correctly become automatic.

Action verbs describe something you are actively doing, for example:

- mhanya (run)

- famba (walk)

When performing the action, you say:

- Ndiri kumhanya — I am running

- Ndiri kufamba — I am walking

However, there are other action verbs that describe a state/condition you are in, not an ongoing action. For example:

- rara (sleep)

- gara (sit)

For these, you use past-tense forms to express the current state:

- Ndakarara — I slept / I am asleep

- Ndakagara — I sat / I am sitting

Reasoning: you have already completed the action physically (closed your eyes, sat down), so the sentence reflects the result of that action, not an ongoing process.

Takeaway for learners:

- Pay attention to whether a verb describes an action or a state.

- Past-tense forms can express a current state for certain verbs.

- With practice, using verbs this way will become automatic.

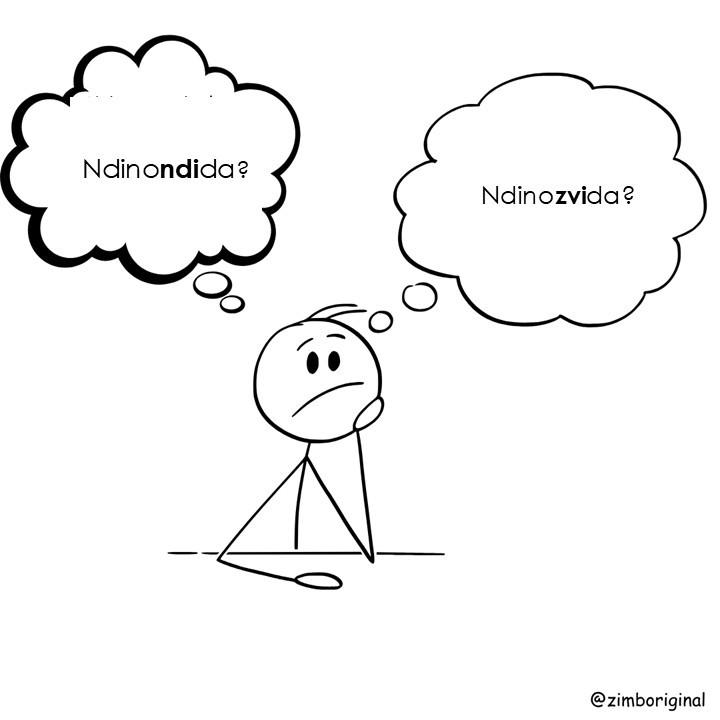

3. Prefixes for personal pronouns behave differently

In some verb forms, the middle part of the verb (the part that shows who or what the action is happening to) follows a clear pattern. It is usually informed by how the noun begins:

- People nouns that begin with mu- use -mu- when referring to one person.

- Those that begin with va- use -va- when referring to many people.

- Other than people, nouns that begin with mu- (trees, body parts, etc.) use -u-.

- Those that begin with mi- use -i-.

- When a noun does not clearly begin with a prefix, the verb usually follows the pronoun used with that noun.

In most cases, this system works well and becomes predictable with exposure.

The tricky part: when the object is a personal pronoun

Things become confusing when the object is not a noun like munhu or vanhu, but a personal pronoun such as me, you, myself, themselves.

When talking about oneself, Shona uses -zvi- in the middle of the verb:

- Ndinozvida — I love myself

- Anozvida — He/she loves himself/herself

When ‘you’ is the pronoun being referred to, we use -ku-:

- Ndinokuda — I love you

The middle parts -ku- and -zvi- thus follow a rule, but the connection to the pronoun isn’t obvious. This is where learners often get stuck. Unlike nouns that begin with mu- or va-, the logic behind these forms isn’t immediately clear, so they are best learned through exposure and repeated use.

A simple way to see the parts of a verb (example: ndinokuda)

| Part of the word | Function | Example in ndinokuda |

|---|---|---|

| First part | Subject concord — who is doing the action | ndi- → ‘I’ |

| First middle part | Present habitual marker — indicates the action happens regularly or generally | -no- → ‘I [verb]’ (e.g., ‘I love’) |

| Second middle part | Object concord — who/what the action is directed at | -ku- → used when ‘you’ is the pronoun being referred to |

| Last part | Verb stem — the main action | -da → ‘love’ |

Takeaway for learners:

- For personal pronouns, the middle part of the verb works like this: -ku- for ‘you’ and -zvi- for ‘myself’ / ‘themselves.’

- Don’t try to apply other rules, just memorize these forms.

- With regular practice, saying them correctly will start to feel natural.

4. Some words don’t mean what you expect: zvangu, zvedu, zvako, zvenyu, zvake, zvavo

Shona has some words that literally mean ‘mine,’ ‘ours,’ ‘yours,’ ‘his/hers,’ ‘theirs’, but native speakers often use them in everyday speech for emphasis or nuance, especially at the end of a sentence.

For example:

- Wakadii zvako? → literally ‘How are you, yours?’ → actually just ‘How are you?’

- Ndiripo zvangu → literally ‘I am here, mine’ → actually ‘I am fine.’

- Tiri kufara zvedu → literally ‘We are happy, ours’ → actually ‘We are happy.’

- Makadii zvenyu? → literally ‘How are you, yours?’ → actually ‘How are you?’

- Ari kufara zvake → literally ‘He/she is happy his/hers’ → actually ‘He/she is happy.’

- Vasvika zvavo → literally ‘They have arrived, theirs’ → actually ‘They’ve arrived.’

These endings add friendly emphasis, reassurance, or affirmation. They’re not strictly grammar; they show how Shona conveys meaning naturally in conversation. It’s a bit like in English when someone asks, ‘How are you?‘ and you reply, ‘Well, I’m alright.‘ That ‘well‘ doesn’t change the meaning, but it adds nuance, tone, and emphasis, similar to how zvangu, zvako, zvavo, etc., work in Shona.

Takeaway for learners:

- Don’t translate these words literally every time.

- Observe how native speakers use them in context.

- Gradually, you’ll use them naturally for emphasis and nuance.

5. Tone can completely change meaning

In Shona, tone is part of the meaning. The same word can mean different things depending on how it’s pronounced. This can be confusing, especially for learners reading texts without context.

I once shared this story on Afrikanists Assemble, Episode 41: I asked my daughter to read a passage aloud. She read musi to mean ‘day’, which is correct in one sense. But I corrected her: with the proper tone, it should have been read as ‘it is a day’, which was the meaning intended in the sentence.

The point is: you can’t always get the meaning from a single word in isolation. Without the full sentence and context, a learner has no way of knowing whether the word stands alone or is part of a larger idea.

Takeaway for learners:

- Always pay attention to tone when reading and speaking.

- Read in context to determine the intended meaning.

- Frequent exposure will make it easier to pick up correct tones naturally.

Wrapping it up

Shona has its quirks, and not everything fits neatly into a rulebook. The key is exposure, repetition, and practice. The more you speak, read, and listen, the easier it becomes to recognise patterns, and exceptions, naturally. Don’t worry if some words or verbs don’t make sense at first. Treat them as ‘non-pattern patterns’ to notice and remember, and gradually they will start to feel familiar. Learning Shona is a journey: keep using the language every day, and the grammar will follow naturally.